You probably know the story.

Expat comes to Vietnam. Lives here for a bit. Decides they want to pay some homage to the culture and isn’t afraid to do the work. Hundreds of dollars and months of practice go by of agonizing repetition of words trying to get those perfect tones just right. …then off into the real world. COMPLETE FAILURE! No one understands a word this expat is trying to say. Why on Earth does Vietnamese Need to be so Difficult?!?

The Language is almost impossible for Westerners to not only pronounce, but to hear.

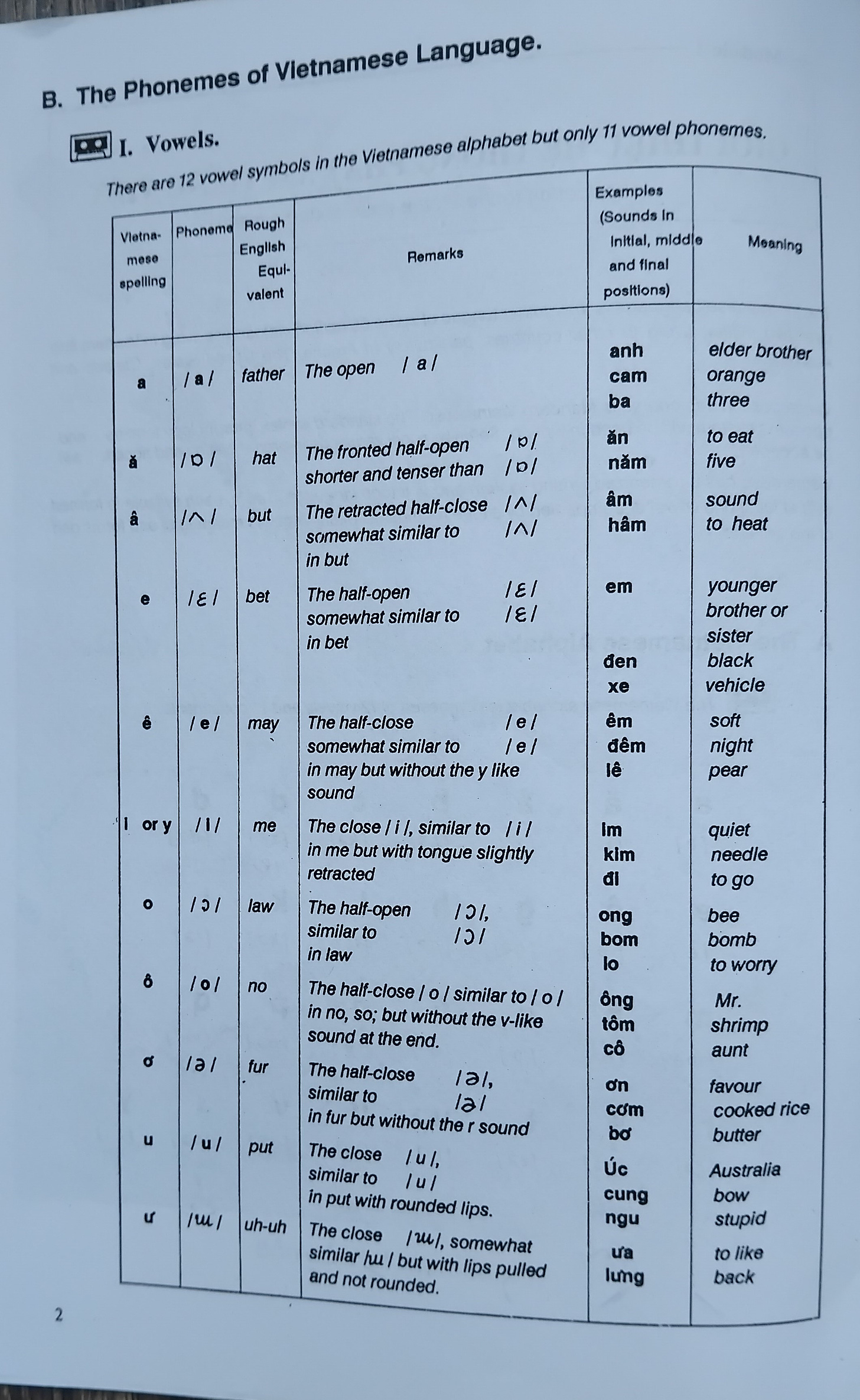

To give you an idea what I mean, I should probably explain the difference between those little marks at the top of Vietnamese words. I am including some quick charts out of one of my text books. In the first chart, is the easiest part of vowels to understand. That is the markings above the vowel that give it the sound. They are called Phonemes, which is just an academic way of encoding vowels to make their precise sound. Unlike English where a vowel can make many different sounds depending on the use, Vietnamese is very precise, where the vowel and Phoneme together make a very specific sound.

a as in father

ă as in hat

â as in but

…

…all very straight forward and easy first day stuff.

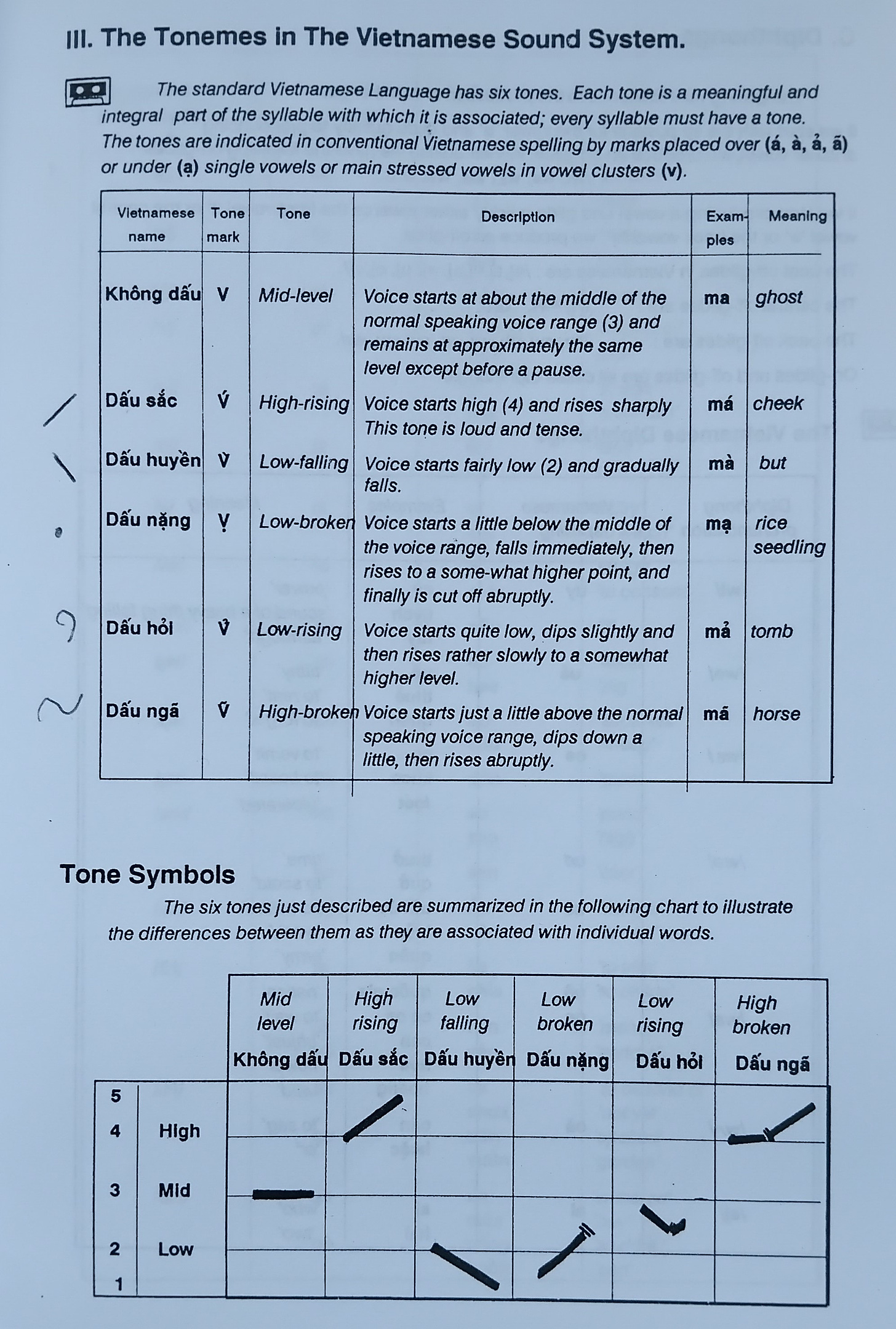

What gets students into trouble are the tones (Tonemes to use the technical term). Every single student I spoke to has gotten stuck right here. This is where most people give up. They may be a couple weeks into a class, or they may have been practicing with an online app for a few months and then realize they never really knew anything because they have never actually spoken to a real Vietnamese person in a normal conversation.

One friend I met from Glasgow joked around and said he tried to learn Vietnamese and now he is completely unintelligible in Vietnamese as well as English.

The tones seem pretty straight forward, but try having a conversation like this. You will quickly find your English cadence and tone start to sneak in. You will ask a question and naturally the final word will end in a rising tone and suddenly you have deeply offended someone’s ancestors.

What about listening to someone.

Most of this can be figured out with a bit of context, but trying to figure out the difference between a broken or falling or rising tone in real time as you are just barely becoming familiar with the language is incredibly daunting. The people who are able to master this skill are incredibly persistent and practice for years to develop their ears as well as their vocal muscles to properly communicate.

There is a great post by John at An Expat’s Thoughts on Life about this and I don’t really want to repeat work that I can just point to. He writes how easy it is to be confused by tones in Vietnamese. He does a better job of fleshing out this issue than I care to.

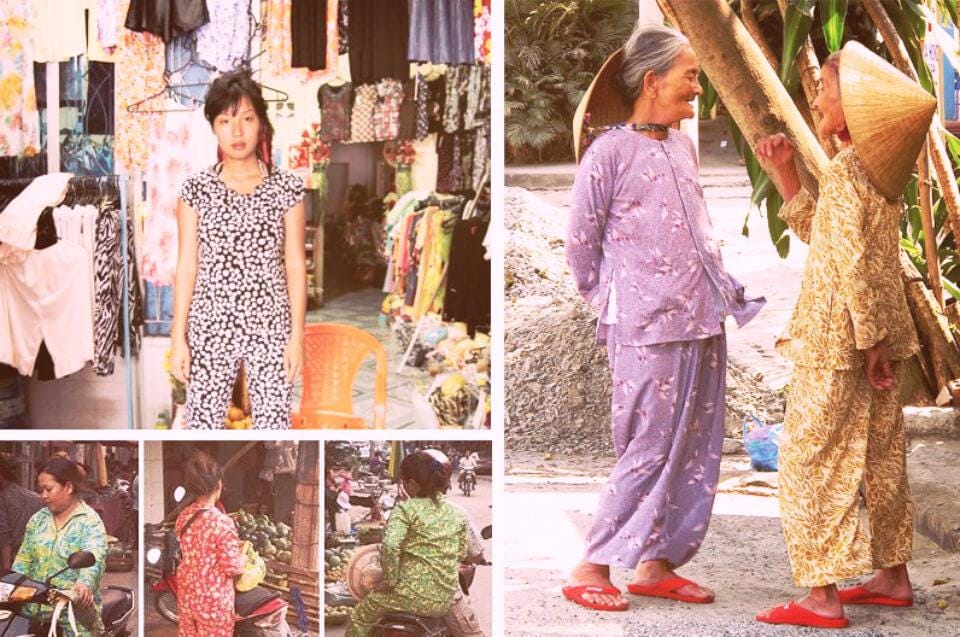

A Western guy who affectionately calls himself Phúc Mập ‘fat and happy’ who is incredibly popular here in Vietnam did a video series about this issue where he had several ‘encounters’ resulting from easy language and cultural misunderstandings. One of his first videos involved him going around the market in his áo dài (traditional Vietnamese outfit) which was actually the ‘around the house’ clothing that I call the ‘countryside auntie uniform’. This is the common outfit for many housewives to wear around the house and is made of very thin fabric. Typically, these outfits are a little more modest, as you can see in the picture below, but Phúc Mập is going for dramatic effect, so he needs to sport the at home leisure wear. Of course, he needs to add the ‘Grab’ motorbike helmet for the complete look.

By the end of the video, to fully immerse himself in Vietnamese culture, he purchased a pet chicken named Bé Đạt (‘be that’ or maybe sounding like ‘that baby’), but his friend Dustin quickly found and ate his pet chicken. Later he picked up a pet duck named Phúc Đạt (which should be obvious what that sounds like in English). Unfortunately, this pet too met an early end (I believe) at the hands of Dustin.

I seem to recall him also looking for sandals (dép - sandals, which interestingly enough is spelled a lot like đẹp - handsome, but sounds completely different, …he would often say he was “đẹp trai nhất Việt Nam” which may have been some other words he was playing with).

Later he was asking for slip-ons, but I couldn’t find that scene in his videos. The English words sound a lot like the words for pink underwear in Vietnamese.

Phúc did a follow up video, a while later, with a similar theme of taking English or Vietnamese words and purposely mistranslating them into something funny. At the 4:30 mark, he tries to say goodbye to his mother in-law and calls her ‘a stupid slut’ by inserting a broken accent over the unaccented verb ‘to go’ and then gets chased off by having a sandal thrown at him.

After tones, Pronouns are impossible

There must be 50 million personal pronouns. They are not simple he/her/she/him… There is the word for uncle from the fathers side, uncle from the mothers side, aunt from the fathers side, aunt from the mothers side, and on and on and on. Here is an article about this issue …and the Wikipedia entry.

This has become such a problem for some of the more experienced expats that it can even be found in a Guardian article from several years back where the author describes his difficult experience going to a family gathering with his immediate family and trying to navigate the maze of family pronouns. This problem is compounded because you need to forget your age relation to the family member and think about your spouse’s position in the family. You may be the oldest person there, but you need to refer to everyone as older brother / sister because your wife may be the youngest sibling. Most people just get around this by using their own name in place of a personal pronoun as Vietnamese often do when they do not know who is older to avoid all of this confusion. This seems elitist in English, but it is very practical in Vietnamese.

Regional Accents

Another factor which really confuses most adults trying to learn Vietnamese is the regional accent. There is a northern accent, central accent, Hồ Chí Minh city accent, a Mekong accent and they are all dramatically different. Most people learn the Northern accent as it is the preferred accent of mass media and academia. Most textbooks and YouTube tutorial videos use the northern accent. Even among Vietnamese, they sometimes need a translator when someone travels from Mekong to Hanoi and no one understands each other. Simple words such as already (rồi) are pronounced ‘roy’ in the south ‘zoy’ in the north and it becomes very confusing very quickly.

Regional Words

Most parts of the country have different words for different objects. Words like pig, rice and so many others are completely different in various parts of the country. In the Mekong countryside, there are slang words for various numbers which you need to pick up quickly because the person will not slow down when quoting you a price at the market. Oftentimes, this just turns into sign-language as a student may have a little difficulty processing a new word instantly.

Slang Words

This one is obvious, because every language has this problem, but nearly everyone learning the language eventually figures it out. The problem with these slang words is that by the time you start to figure out the plethora of the many problems above, a persons brain is so fried, they have trouble absorbing these words.

Vietnamese is certainly not for the faint of heart and requires a lot of practice. That is why most language schools consider Vietnamese to be among the most difficult languages to learn.

I have probably forgotten some other difficulties, so I may add to this article later. If I do, I will try to mention the addition in the notes. If you have any other stories of language difficulty, I would really love to hear about them and I may even add them to the article in a later update.

Well done, Brian. And thanks for the link to my earlier (by six whole days) article.

I know well the extended family trap, though I didn't know about using one's own name instead of em or anh. I have a hard time referring to myself as "em" when I'm older than all of my brothers- and sisters-in-law, but my wife is the youngest sibling. It changes again when dealing with parents-in-laws and their siblings and siblings' children 'cause my mother-in-law is the oldest.

I'm going to use tôi to refer to myself from now on.