For several weeks, my friend John, from An Expat's Thoughts on Life, and I have had the occasional discussion about the old Vietnamese laws. It became a source of deep fascination after reading Nguyễn Văn Huyên’s book The Civilization of Vietnam. Our discussions on the old laws’ allowable reasons for divorce and some of the interesting familial rules seemed to shed a bit of insight into how Vietnamese currently live. At some point, John suggested that I might be interested in researching this and writing an article. This is the culmination of several of my articles, inspired by these original discussions, about the legal and economic systems of Vietnam.

As I got into the research, it became more involved than I had anticipated. If I hoped to properly explain some of the old customs and laws, I would need to write a series of articles. I began knowing only what I read in that one book, which meant some digging was in order. After looking into some background of the law for the article Understanding the Origins of the Vietnamese Legal System, I can finally address some of the weird-to-a-westerner aspects of the folk law as well as Confucian law and how each was implemented under the Vietnamese monarchies.

I don’t really know how much of the Confucian rules can be applicable to other Chinese-derived cultures. I suspect much of it is universal, but much of the interpretation I have studied has a unique Vietnamese spin, so some caution should be considered when trying to make generalities.

Originally, ideas such as divine beings or Heaven (天 Tian - The Chinese word for Heaven) seem to mostly be used as religious analogies to explain philosophical concepts, very similar to the Greek Philosophers. Much of the interpretation of Confucius has evolved in modern times because these values have been updated and reinterpreted by modern secular scholarship. Mainstream scholars have replaced some of the mystical aspects of the system of beliefs and down played some of the Emperor or ancestral worship in favor of general submission to the state. In addition, aspects of filial piety (respect owed to one’s parents and ancestors) seem to be replaced, in some countries, with the concept of national brotherhood, although submission to the family unit remains strong. The core of the message remains universal as described in Understanding the Origins of the Vietnamese Legal System as:

“Confucianism is a philosophical and ethical system developed by Confucius in the 6th century BCE, and rooted in Chinese tradition that emphasizes moral values, social harmony, and proper conduct. The concepts of ren (benevolence or humaneness), li (proper behavior or ritual propriety), and xiao (filial piety) are central to Confucianism, stressing the importance of education, family loyalty, and respect for elders and ancestors. It advocates for a hierarchical society based upon merit where rulers govern by moral example. By promoting virtues such as honesty, integrity, and righteousness, Confucianism aims to create a harmonious and orderly society, influencing both Chinese culture and that of other East Asian societies.”

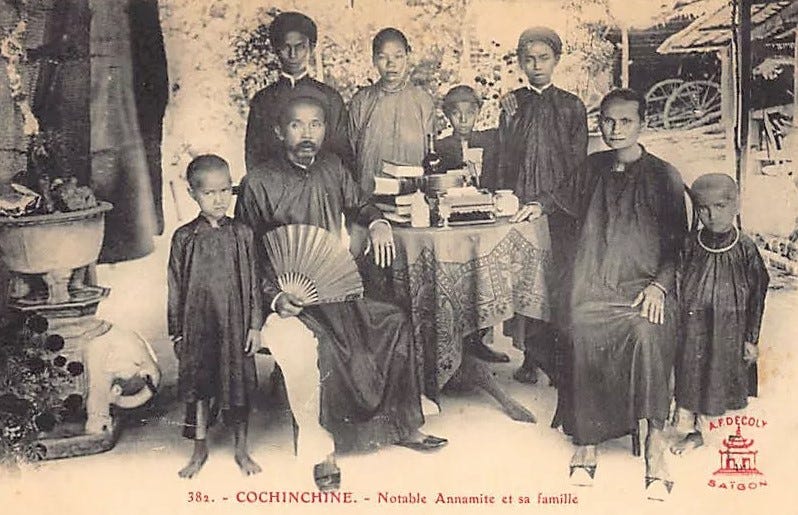

The Vietnamese Family and Clan

It is important to understand that, under Confucianism, the authority of the family was the bedrock of moral values. Children and wives are expected to submit to the authority of the father. The father was expected to submit to the clan patriarch. Obligations to the community built upon these core family values. The community was expected to submit to the authority of the Emperor, who was expected to rule with wisdom and justice for the betterment of the whole country.

The clan is where a person derives their family name (Họ - the Vietnamese word for surname). Within the clan would be several families that branch off of the clan. It was the extended family unit which holds property in common, including the ancestral graves as well as the ancestral home, typically the house where the grandfather or great grandfather lives, along with their family. Inside the ancestral home was the family ancestral temple (Nhà thờ). When Vietnamese talk about returning home or going to their hometown, this is the building to which they are often referring.

The Grandfather or Great Grandfather (Trưởng tộc – Clan Chief) has the responsibility of resolving family disputes as well as having the final say regarding marriage, mourning or any other family business. He has the final say at the family council, which is typically the clan chief and three relatives of the paternal line, or if they are not available, three notable friends of the family. This person also has the role of patriarch (tộc trưởng). When the grandfather dies, his eldest son becomes the new patriarch.

The family chief (gia trưởng) exerts moral influence over his children and grandchildren. Then, when males have their own families, they become family chief over their own family line. The same lineage rules apply within the family as within the clan; when the father dies, he is replaced as the family chief by his eldest son. His mother will then answer to her eldest son as she did to her husband, and the younger children become his responsibility. This obligation is released when the siblings marry and establish their own separate household.

Huyên describes the rule of the father like this…

“At first when the paternal power was absolute, the head of the family managed the property of his family with absolute authority. His wife and his children had to work to increase the family wealth and had no assets of their own. He had absolute rights over the individual of all the members of his family. He could sell his children, hire them out, and give them as collateral to his creditors. He could do the same with his wife.”

The family rule of “I brought you into this world and I can take you out of this world.” was dialed up to 11 when, in the ancient family law, the father had the final say regarding marriage as well as the right of life or death over his children.

The only way around the direct rule of the father was to establish an independent household. Initially, minors were given very few rights, so the only way for a child to become emancipated was to marry and acquire his own property, unrelated to the family estate. Unemancipated minors still living in the family estate only owned property if their father allowed it.

The rights of adulthood were not established based upon an age (although it was typically at 18-20), but upon the ability of the young person to take upon themselves the obligations of the village. Once this person began paying taxes and performing civic duties, they were considered an adult and due the rights associated with being an adult. Rights of a male would include participation in receiving his portion of communal land for rice farming, a seat in the đình (communal meeting house), and participation in feasts.

Oftentimes, the community held much of the farmland which would be divided for cultivation among the adult (married) men of the village. Taxes would be assigned down to the village level and each adult man was assigned a portion of those taxes. Certain civil administrators (Mandarins) were assigned to a geographic region to settle disputes and insure taxes were collected. He was required to record legal documents and write official reports of serious crimes within his region.

Marriages were typically arranged around the age of puberty (12-13 for girls and 15 for boys). Some of these marriages would be arranged very early to cement social bonds between families. The idea behind an early marriage was to have a large family, which was considered to be a happy family. Celibate men were disapproved of for not maintaining filial piety, while celibacy among girls was highly honored if the purpose of that celibacy was to take care of her parents or younger siblings.

The family had a legal obligation through the older system of filial piety to obey the wishes of the patriarch. The code of the Lê dynasty (established at the end of the 15th century) explicitly punished the children and grandchildren who disobeyed their parents or grandparents. The Gia Long code (established in 1812) was an attempt to curtail excessive behavior by saying that children must conceal the faults of their parents, except when those crimes impact the security of the state. Children were, however, allowed to respectfully disagree with the patriarchs. Children were still obligated to honor the will of the patriarchs, even after the patriarch’s death. This obligation endures today when some parents expect their children to go as far as lying on their behalf to protect the parents from conflict.

The Gia Long code sought to bring a limitation to this power by limiting the ability of the father to kill his children without repercussions, though the law still favored the actions of the father over the son. In the Gia Long code, the punishment for beating a child to death was 100 strikes of the cane (trượng). The punishment for anyone who sold his wife was 80 strikes of the cane. If the dead child was known to be habitually insubordinate, the father was excused. Patricide was dealt with much more severely. If the child was found guilty, he was sentenced to a slow death. If the child merely contemplated the crime, but did not succeed, the punishment was decapitation.

Inheritance

The patriarch is able to appoint any heir he deems fit to receive the family estate. With the inheritance comes expectations. From the resources of the estate, the heir is responsible for the maintenance of the ancestral home. If you ever walk into one of these homes, you may notice a shrine near the front door where there may be one or several altars with pictures of grandparents on the wall. This is the ancestral cult. From this home, grandchildren are expected to occasionally give offerings and burn incense on the anniversary of the ancestor’s death (especially the first year anniversary). Incense bowls are never emptied and are filled with ash to symbolize the incense offered in previous generations. The heir is expected to provide incense, candles and any other object necessary to perform the ceremonies.

The worship of the ancestor is not like praying to the gods at the temple. It is a respectful checking in to make sure the ancestor is happy and enjoying their afterlife. Often times, money, clothing and luxury items are sent to the ancestor via some paper replicas which are thought to manifest in the spirit world for the ancestor to enjoy. The worship of the ancestor seems to be focused upon giving something to the ancestor as a thank you for everything they have given during their lives. This is contrasted with the worship at the temple, which seems to be about requesting something; luck, guidance, health, etc.

The ancestral home is considered sacred and not to be sold until the sixth generation without the explicit agreement of the family assembly (at six generations, it is presumed that anyone who knew the original ancestor is already dead). This authorization is typically granted in the case of excessive damage to the ancestral home. The cult is considered active four generations before the current generation and four generations after (meaning the cult typically extends to great grandparents and great grandchildren of the current patriarch). This is why you will only see ancestral pictures of grandparents and great grandparents of the current keeper of the ancestral home. There is a table with four chairs before the altar, which I assume is for the four ancestors (father, mother, grandfather and grandmother). After this point, the ancestral spirits no longer need to watch over their family and are released from the ancestral home into the next world.

If there is no natural son (meaning the family had no physical heir), the person may wish their ancestor worship to be moved to a communal temple or pagoda. A photo of that person is kept in a special room to honor the dead who were not able to be honored in their own ancestral home. The person administering the estate would make a donation to a temple in the form of cash or land, for the community to perform the rituals and sacrifices on the day of the persons death to give that spirit rest. Typically, temple photos are filled with young faces, occasionally children, along with some poor individuals who were never able to establish a family. I am not sure if every temple has these rooms, but they are typically in the back in a private room. Below the photo, you may see a candle (electric candle today) along with an inscription of their name and date of death. I have been warned that people are to stay out of this room so they don’t accidentally disturb the rest of the spirits, thus creating upset spirits.

Sometimes a person might inherit a community temple with a small portion of land. The temple may have been their grandfather’s gift to the community. In exchange for maintaining the temple, they are given land associated with the temple for their own personal use. Typically, this is not a gift as much as it is a responsibility because if the property associated with the temple does not generate sufficient revenue, the person is still responsible for the temple’s maintenance.

Temple maintenance may involve a yearly fund-raising drive, going door to door for a day collecting money to give to the poor in the community or to support some construction in the temple. Although Vietnamese may occasionally have the reputation of being thrifty, people are not known to cheap out on their civic duties. This position grants the person a huge amount of respect which can be redeemed if the family ever requires a favor or falls upon hard times. In Vietnam, respect trumps wealth.

Family Life

As mentioned above, the rule of the patriarch over his wife was absolute.

As mentioned by Huyên:

“According to the moral law”, “[the wife] had three obediences: at home she follows her father, after marriage she follows her husband, and when widowed she follows her son.”

At no point in her life was a wife considered to be autonomous, although there was quite a bit of freedom in the role of first wife.

Polygamy was quite common in pre-colonial Vietnam. With the introduction of Western values and Christianity, it became “out of fashion”, but still occasionally practiced. Even up to the French Colonial Period, polygamy was still practiced, but without the status it would have received in earlier days.

There are two categories of wives, the first wife (vợ cả) and the second rank wife (vợ lẽ). There could be only one first wife, but there was the possibility of several second rank wives, called oldest sister and numbered by seniority. There was also the possibility of concubines (hầu), who were bought but not married. All of these spouses would leave their families and join the family of the husband. The first wife received all of the status, including a place at the right hand of the husband in religious matters. The first wife was allowed to sit at the family table, whereas the second rank wives would not.

The first wife was the head of the household. You may recall my very first article, Vietnam: The Matriarchal Patriarchy, in which I talked about the wife controlling the purse strings of the family. This is where it goes back to – this wife was the family administrator. She was in charge of all income, collected rents, and settled all expenses. She was also the mother of all children (including the children born to other wives). She was responsible for the education of the children, though the husband’s will was supreme here too. She was in a highly respectable position because she managed the household economically. She was also considered to be the collaborator of the husband, because she maintained the household, which husbands were thought to neglect.

The purposes of having multiple wives were primarily to have additional children or to add to the family’s financial security by adding to the workforce. Of course, a certain amount of vanity played into the decision, as one would expect when an older man finds a young spouse.

If a husband dies and a widow wished to remarry rather than live under the care of her eldest son, she would lose all rights to her children and the children would go to the home of the husband’s closest relative. The Civil Code of Tonkin shifted the rights to allow mothers the ability to be able to take parental custody of her young children if the husband dies.

Family Law

Of course, sometimes a patriarch gets a “bad” wife. Early reasons for a divorce with cause under the Lê dynasty code include the following:

She is sterile, causing the husband not to fulfill his filial piety obligation.

She talks too much, is excessively jealous, and speaks ill of others.

She suffers from a horrible disease and may pollute the sacrifices offered to the spirits.

She behaves badly.

She steals, especially if this theft causes harm to her family.

She shows disrespect towards her parents in law.

She does violence to her husband or his parents.

As arcane as the Gia Long code sometimes seems, we see in the modifications to divorce law a much more liberal legal implementation than earlier Lê dynasty code by curtailing some excesses:

If the parents of the wife are no longer alive to take her back

If the wife has already observed the mourning custom of one of the husband’s parents.

If the husband is poor when he married his wife and subsequently became rich.

Today, the laws are even more beneficial toward women because the rules about asking parents to marry or asking parents for permission to buy a house have been eliminated. In addition, the laws which allowed the mother-in-law to exercise tyrannical authority have been removed. Portions of the law which assigned blame to the wife have been removed in recognition that both spouses may be at fault when a marriage dissolves. The laws are currently much more egalitarian among the genders, but the ancient moral law remains in the minds of some Vietnamese, occasionally allowing some previous excesses to still be practiced.

Conclusion

Vietnamese society is a work in progress. Initially, rules of tribal society consisted of societal expectations. This first society was egalitarian with men and women sharing responsibilities pretty evenly among the family. The layer of Confucius’ ideals were added to codify and add some structure to family customs as well as cement the rule of the Emperor as supreme. This added a layer of patriarchy because the father became the ideal figurehead of the Confucius family and maintained absolute authority.

When the Vietnamese regained their independence following nearly a millennia of Chinese rule, there was a reversion to egalitarianism, though the father still maintained absolute authority. Through a series of reforms over several hundred years, this authority was refined to consider the rights of other family members. Over time, Western ideals were added as an additional layer to incorporate personal rights into the family. Currently, Vietnam is much more egalitarian with an increasing amount of shared responsibility between the spouses. Despite more equality among the genders, we see much of the ancient ancestral traditions still in practice today with reverence for the older generations in the form of ancestor worship.

Even though more than a century has passed since some of these laws were enforced, it is clear that their influence still remains in Vietnam today. Hopefully, insights of how certain customs influence Vietnamese culture are clearer as we see them affect society in unexpected ways. By exploring some of these unusual or archaic rules, we can better understand some of the puzzling behavior we occasionally see in Vietnam today.

Thank you for reading Postcards from Vietnam! I always enjoy reading what people think about these articles, so please leave a comment or hit the like button to let me know you enjoyed the article.

Is there a reason why endogomy was not practiced in East Asia despite having a clan based society? Is there a strong taboo against endogomy in general?

Goodness me, I’m so glad I wasn’t brought up in Vietnam in those days, it was bad enough that our father wouldn’t allow us to marry a Catholic! As you indicated things have gradually changed, but I know one thing for sure, which would be similar in our family, and that is if either of my husband or I die, which I know we will one day… that our children would definitely look after whomever was left.