This article is part three of a four-part series about the life of Hồ Chí Minh.

The first article explains the forces which influenced him and describe his early days as a young man discovering his purpose in life.

The second article explains his involvement as an agent of the Soviet Comintern and his navigating a civil war while trying to balance Communist and Western loyalties.

These events positioned Hồ for the pinnacle of his life’s work, the Independence of Vietnam.

Vietnamese Struggle for Independence

In late August 1945, the Việt Minh launched the August Revolution, also known as the August General Uprising, against the Empire of Vietnam (the Japanese). This revolution immediately followed the August 6 and 9 detonations of two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These bombs sent Japan into chaos and forced immediate surrender to the Allies, ending WWII in the Pacific Region. The Allies were distracted with securing the Japanese homeland, while countries still occupied by Japan were temporarily ignored.

Within two weeks, the Việt Minh forces seized control of most of the cities around Vietnam, including the capital of the monarchy, Huế, and the other two Vietnamese capitals of French Indochina that made up the remainder of Vietnam: Hà Nội and Sài Gòn.

When the Việt Minh gained control of Huế, they threatened to kill Bảo Đại if he didn't abdicate. He messaged the Allied leaders for support and never received a response. Realizing he had no support, he abdicated on August 25th. He gave the Việt Minh the Emperor sword and seal in a ceremony transferring the "Mandate of Heaven". The Mandate of Heaven is the heavenly authority to lead a country and important in the Confucius belief system. After the abdication, the Việt Minh asked Bảo Đại to go to China. He lived there for about a year before choosing to move to France.

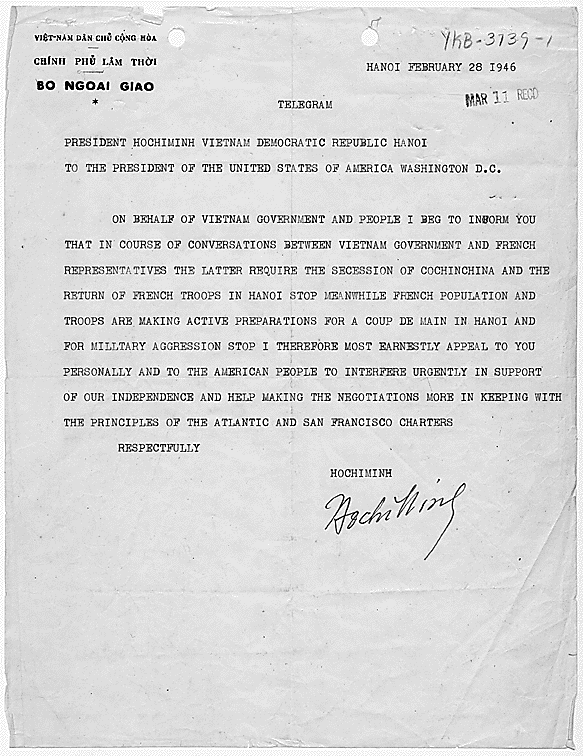

Hồ Chí Minh declared the independence of the new state of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN) on September 2, 1945. The declaration featured references taken directly from the U.S. Declaration of Independence, such as “All men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights”. It also included references to the French Declaration of Human and Civil Rights. Hồ Chí Minh assumed the role of Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam. Hồ also sent a Telegram to U.S. President Harry Truman, appealing to the people of the United States for help but never received a response.

The new Democratic Republic leadership moved to solidify political support. Võ Nguyên Giáp issued decrees on behalf of the DRVN to dissolve rival political parties and movements, including the Trotskyists (communists who opposed the Soviet aligned Việt Minh communists). He allowed Ty Liêm Phóng to arrest individuals considered dangerous, he dissolved trade unions, and he centralized the economy under state-controlled committees.

In an effort to unify religious factions, Hồ sent a letter of support to the newly appointed Vietnamese Bishop, Lê Hữu Từ, stating "There is a new Catholic leader who follows in Jesus' footsteps, is crucified to help the laity to sacrifice and fight for the freedom and independence of the country." Although the Catholic religious minority mostly joined with Diệm’s southern government, these overtures would help reintegrate Catholics into Vietnamese culture following reunification by giving them a place in the DRVN.

The French Attack

On September 23, 1945, the French attacked Saigon causing the British commander, General Sir Douglas Gracey, to declare martial law. The Việt Minh responded by calling for general strike.

Chinese National Revolutionary Army troops arrived in Hanoi with a force of 200,000 men to accept the Japanese surrender. The situation with the Chinese Nationalists and the Việt Minh grew tense due to ideological differences. Chiang Kai-shek likely knew he would need those troops back soon because, the following month, the Nationalists and the Communists would again go to war in China. Hồ Chí Minh saw the Chinese Nationalists as only a bunch of additional mouths to feed when his own people were already struggling to get enough food. The population of Hanoi swelled with 300,000 Vietnamese mobilized in the streets to support Hồ Chí Minh, 200,000 Chinese troops, plus an additional 120,000 British, French and Japanese troops. Hồ implemented fasting for one day out of every ten to preserve the food supply.

In an effort to pacify the growing anti-communist attitude that surrounded him, Hồ Chí Minh made a statement expressing his desire to unite other factions into the Vietnamese government:

"When the Provisional Government was organized, there were comrades in the Central Committee elected by the National Congress who were supposed to join the Government, but they automatically resigned to make way for patriotic personnel who were outside the Việt Minh. It is a carefree and good gesture, not greedy for status, putting the interests of the nation and the people's unity above personal interests. It is a commendable and respectful gesture that we must learn."

The French agreed to return all Chinese land taken during the “Unequal Treaties” period with the Sino-French Accord of February 29, 1946 in exchange for the Chinese Nationalists returning to China. Even though the French had lease rights to the leased territory of Guangzhouwan (present-day Zhanjiang) until 1997, they agreed to return it to the Chinese early. With the Chinese leaving, French troops would soon replace the Chinese troops in Vietnam.

Soon after, Hồ reached a compromise to dissolve the Communist Party and hold elections for a coalition government. On March 6, he went to France to negotiate an agreement to recognize Vietnam as an autonomous state. The French would initially send 15,000 troops to replace the Chinese army, with the condition that 3,000 of those troops would be withdrawn each year. Hồ spent nearly four months negotiating an agreement at the Fontainebleau Conference. The Conference ultimately failed and representatives from other factions returned to Vietnam. Hồ and Colonial Minister Marius Moutet remained to sign a Vietnamese French Provisional Agreement. They needed to reach a permanent agreement before the end of the year, which never happened.

In late September, the United States withdrew all intelligence personnel from Vietnam, thus severing ties with the DRVN.

On November 23, hostilities resumed as the French Navy artillery bombarded the city of Hải Phòng, clearing the way for a march to Hanoi. By December, the French army sent ultimatums for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam Army to disarm and hand over rule to the French. On December 19th, Hồ Chí Minh called for nationwide resistance in an 8pm radio message, marking the beginning of the First Indochina War.

In March 1947, Hồ Chí Minh moved the Party Central Committee to Việt Bắc, the rural mountainous region north of Hanoi. During evacuation, he commanded the destruction of all infrastructure, so as not to leave anything behind to aid the French.

The Vietnamese National Army had very few weapons; they only had a small cache of weapons that were salvaged or captured during the war with the Japanese. Forced to resort to forest blacksmiths, the Vietnamese Army created rudimentary weapons: muskets, machetes and Molotov cocktails.

The Vietnamese National Army’s tactics caused the enemy to become bogged down with guerilla attacks to grow increasingly tired of war. The success of these tactics led to their redeployment during the Second Indochina War (with the Americans). While still in Paris, Hồ would describe future Vietnamese tactics:

"It will be a battle between elephants and tigers. If the tiger stands still, it will be trampled to death by the elephant. But the tiger did not stand still. During the day it hides in the forest and goes out at night. It would jump on the elephant's back, tear off large pieces of skin, and then it would run back into the dark forest. And gradually, the elephant will bleed to death. The war in Indochina will be like that."

A French visitor later recalled a quote from Hồ: "You can kill ten of my men for everyone I kill of yours. But even at those odds, you will lose and I will win.”

With the Vietnamese driven to Việt Bắc, the French sought to re-establish their former colony. The French called Emperor Bảo Đại to return in 1949 after they had again secured the major cities of Indochina. I imagine the French saw Hồ Chí Minh and the Việt Minh as just another revolutionary group which needed to be suppressed, similar to the three-decade campaign to suppress early revolutionary Đề-Thám, leader of the Yên Thế Insurrection.

In the early 1950s, after the Soviet Union recognized the DRVN, Hồ took a three-month journey to Moscow and China to meet with Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong to secure international support. Mao agreed that his new country of The People’s Republic of China would provide training, weapons, and munitions needed to fight the French.

When Hồ returned to Vietnam, he attended the 2nd National Party Congress held in the middle of February 1951 in Tuyên Quang, where the Congress brought the Communist Party back into public operation. This time, the name changed from the Vietnamese Communist Party to the Workers’ Party of Vietnam.

During Hồ’s time in France, the Việt Minh proved their guerilla war mastery, fighting the French. Rather than face the Việt Minh in a long war of attrition, where the Việt Minh had the jungle advantage, the French came up with a plan to create a defensive fortress, to draw the Việt Minh out to be pummeled by unrelenting French artillery. In July 1953, French General Henri Navarre initiated a series of military operations in Indochina, but the French found themselves unable to decisively defeat the North Vietnamese. In November 1953, Navarre launched Operation Castor to capture Điện Biên Phủ, aiming to draw the North Vietnamese into a decisive battle.

General Võ Nguyên Giáp’s strategy involved surrounding and besieging the French stronghold with superior numbers and better positioned artillery. He squeezed the French off from being resupplied by pummeling the airstrip with higher ground artillery. No one ever predicted that the Việt Minh would be able to carry their own artillery, plus the tens of thousands of shells, across roadless jungles and through unrelenting rivers.

After a several-month siege by the Vietnamese, the French surrendered on May 7, 1954. Approximately 11,000 French soldiers surrendered to the Việt Minh, only 3,300 of which survived imprisonment. This defeat marked a significant turning point, as it forced France to exit Indochina.

1954 Geneva Accords

The 1954 Geneva Accords concluded the war between France and the Việt Minh. The Accords temporarily divided Vietnam at the 17th parallel despite opposition from the DRVN, who agreed to divide the country only until free elections could reunify Vietnam after the French left. Initially, the North preferred a more defensible boundary closer to the 13th parallel or even along existing military lines but accepted the 17th parallel to end the conflict and avoid further fighting.

The accords were tense. According to CBS News correspondent Alexander Kendrick, the American delegate, John Foster Dulles, refused to shake hands with Chinese delegate Zhou Enlai. Dulles left before the conference on Indochina began after the earlier Korean conference yielded little results.

There were nine different factions represented in these Accords. The Việt Minh had their own faction, and another faction, The Vietnamese National Delegation, went to the Accords to represent the general interests of the Vietnamese people. Trần Văn Đỗ led the Vietnamese faction. Representatives of Laos, Cambodia and the Vietnamese National Delegation were not allowed to participate in conference negotiations. Đỗ refused to sign the accords on the grounds that foreign powers were dividing Vietnam, thus putting Vietnam in a dangerous position. He had clear vision into the future that accurately predicted the problems of the coming decades. A delegation representative would later say:

"The signing of the agreement between France and the Việt Minh had provisions that seriously endangered the political future of the Vietnamese nation. The agreement ceded to the Việt Minh areas where the national army were still stationed and deprived Vietnam of the right to organize defense. The French Command set the date of the election without an agreement with the Vietnamese national delegation...

“The National Government of Vietnam requested the Conference to formally acknowledge that Vietnam solemnly opposes the signing of the Agreement and its provisions that do not respect the deep aspirations of the Vietnamese people. The National Government of Vietnam requests the Conference to recognize that the Government gives itself the right to complete freedom of action to protect the sacred rights of the Vietnamese people in the realization of Unity, Independence, and Freedom for the country."

The Accords set aside a 300-day period where people could move freely within the divided country before the election. Most of the 800,000 to 1 million people of the Catholic minority migrated to the south, along with an additional 200,000 people opposed to Việt Minh rule. In exchange, approximately 130,000 people, mostly Việt Minh resistance forces, moved north.

In 1955, the French government in Vietnam dissolved and was replaced by the Republic of Vietnam. Emperor Bảo Đại permanently moved to France, because the French no longer needed him in Vietnam.

The Geneva Accords scheduled general elections in July of 1956. The United States opposed the Accords, supporting the Republic of Vietnam’s refusal to hold free elections. South Vietnamese Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm rejected elections over concerns of fair conditions in the North and potential electoral manipulation. The population of Northern Vietnam greatly outnumbered the population of Southern Vietnam, giving the Việt Minh an advantage.

Neither Northern nor Southern factions could agree upon reunification terms when several countries pushed for the United Nations to supervise the election. The Soviet representative rejected the terms unless they guaranteed equal representation among communist and non-communist members. Neither side could come to an agreement, so the temporary borders became permanent.

Up to this point, the U.S. had only been nudging politically. They were far too busy concluding the war against Japan, followed by the monumental effort to rebuild Japan. Tensions rose as communist forces began taking large portions of Eastern Europe and Asia. This began an ideological war, with the US taking a stand against the communists starting in Korea and later moving to Vietnam. Like a series of dominos, the nations of Asia were being swept into the communist camp. Korea and Vietnam became battlegrounds of an ideological proxy war between Eastern Communists and Western Capitalists.

The next article will discuss the circumstances which progressed from the US supporting the Southern Republic with advisors to a decade-long war between the US and the Việt Minh and will discuss Hồ Chí Minh’s final days.

Addendum

There is a possible scenario which could have led the U.S. and Vietnam to avoid war. Some historians argue that the U.S. involvement in the war against Vietnam could have been avoided because Hồ Chí Minh favored nationalism over ideology. This issue remains controversial, but I will try to present both sides as fairly as possible.

Originally, this section only consisted of the first three paragraphs with the Patti quotes and was imbedded within the article. Unfortunately, adding more paragraphs ruined the flow, so I moved the snippet here as a type of addendum.

An Opportunity for Peace

U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel and OSS Officer who headed operations in Hanoi, Archimedes Patti, declared the period following Vietnamese independence pivotal in his 1980 book Why Viet Nam? Prelude to America’s Albatross. Hồ seemed to be flirting with different ideologies to determine which global power would give Vietnam a better deal.

“Ho said that the Americans considered him a "Moscow puppet," an "international communist," because he had been to Moscow and had spent many years abroad. But in fact, he said, he was not a communist in the American sense; he owed only his training to Moscow and, for that, he had repaid Moscow with fifteen years of party work. He had no other commitment. He considered himself a free agent. The Americans had given him more material and spiritual support than the USSR. Why should he feel indebted to Moscow? However, with events coming to a head, Ho said, he would have to find allies if any were to be found; otherwise the Vietnamese would have to go it alone.

It was by now very, very late, and again I rose to leave. Ho pulled out his old pocket watch to look at the time. Would I stay a minute longer? And again I sat down. Ho asked me to carry back to the United States a message of warm friendship and admiration for the American people. He wanted Americans to know that the people of Viet Nam would long remember the United States as a friend and ally. They would always be grateful for the material help received but most of all for the example the history of the United States had set for Viet Nam in its struggle for independence.”

American War in Vietnam apologist, Dr. Mark Moyar questions the revelations of Patti’s book. He said the world changed between 1965 and 1975. Several key events happened over those ten years, including the Sino-Soviet split, the Chinese Cultural Revolution and the Cambodian Civil War which worked together to create tension between the Chinese and the Vietnamese. Prior to 1965, Moyar states both China and Vietnam were working together to actively promote communism throughout Southeast Asia, with countries like Indonesia or Thailand being the next Communist targets. He claims that authors such as Patti or George Ball changed their involvement when writing their biographies to wash away their sins from the historical record.

Is Moyar correct when he dismissed Patti’s opinion as second thoughts aimed at justifying his involvement in the war? Could Moyar be right that it became fashionable to criticize the war? I tend to believe Patti’s autobiography because it is his lived experiences. It seems disingenuous to reject a first-person account without contrary evidence.

Right away, I start to question Moyar’s narrative because he references Hồ’s frequent visits to China during the Chinese Civil War but seems to have little understanding of the political situation between the Soviets and the Chinese during that time. Moyar seems to believe that Hồ was allied with the Chinese and quickly dismissed the thousands of years of bad history between Vietnam and China without understanding the nuance of the relationship. Hồ acted as a Comintern agent when he went to China but that was on behalf of the Soviets, not the Chinese. During the Sino-Soviet split, Vietnam ultimately took the side of the Soviet Union.

Maybe the Domino Theory was correct in 1965, but after the Sino-Soviet split a few years later, any idea that the Communist world was united is laughable. You only need to look at the actions of the U.S. who were preparing to withdraw from Vietnam in the late 1960’s. Trying to blame the failure of the war in Vietnam on “the Media” or politicians shows a lack of understanding of the political situation at the time. After the Nixon China visit, the Domino Theory became irrelevant. There was no need to continue the war in Vietnam. Nixon got to the root of the issue by dividing the Soviets and the Chinese to stop Communist expansion. That was the reason the U.S. lost interest in the war, it no longer served a strategic purpose.

I already said too much, I will cover the rest of this issue in the next and final article.

On the domino theory, I believe Lee Kuan Yew attributed Singapore's ability to develop to US intervention in Vietnam. He believed the theory was sound not due to a fear of monolithic communism but rather due to the fragility of Southeast Asian states during the sixties. Given the Confrontation with Indonesia, the insurgency in Thailand, and SIngapore's recent divorce with Malaysia, the fear was that communism could advance regardless of any squabbles between the two communist powers. After the Indonesian coup, the fear subsided (the US DoD identified Indonesia as the paramount domino), but the US's credibility was arguably intertwined with the fate of South Vietnam by that point