In the first article of this multi-part series about Hồ Chí Minh, I discussed his influences and early days.

This article introduces young Hồ Chí Minh finding his purpose in life. Hồ finished his formal colonial education and spent approximately a decade traveling the world and writing about his life’s mission, the independence of Vietnam. Now at a crossroads, he finds that working within the French colonial system is not giving him the desired results. Soviet Agents offer him the opportunity to go to Moscow and make the connections he desperately needs to accomplish his dream.

First Visit to the Soviet Union

By May 1922, Hồ caught the attention of Dmitry Manuilsky, who agreed to sponsor his first 1923 trip to the Soviet Union. Hồ went to Moscow as Chinese merchant, Chen Vang. While in the Soviet Union, he participated in the Fourth Congress of the Communist International (Comintern). The international organization founded by Lenin in 1919 to advocate for world communism, also known as the Third International. Early presidents included Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky. There he met Lenin, became a member of the Southeast Asia Committee of Comintern and their secret agent.

In June 1923, Hồ attended the Eastern Communist Labor University in Moscow, where he trained in Marxism, propaganda, and the tactics of armed uprisings. At the October 1923 First Conference of the International Peasants, fellow members elected Hồ to the Executive Committee and the Presidium of the International Peasants Council.

At the 1920 Second Congress of Comintern, members defined the organization objective as a "struggle by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and the creation of an international Soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the state."

First Visit to China

In June 1924, Hồ journeyed to China to give lectures and participate in Comintern committees under the pseudonym Ly Thuy. He joined the Oriental Committee overseeing the Southern Department. Reports of Comintern seem to indicate that Hồ broke with party ideology when he said French colonialism caused the class struggle in Vietnam and not the landlords and monks. Hồ interpreted Lenin’s Treatise on Colonial Nationalities to mean nationalism could be a way to achieve communism. People within Comintern thought that his line ran contrary to their doctrine. He would need to address these concerns the next time he returned to the Soviet Union.

Some say that in June 1925, Hồ betrayed his old family friend and ideological mentor, Phan Bội Châu to French Secret Service agents in Shanghai for 100,000 French piastres. Hồ hoped to incite anti-French sentiment and gather funds to start a communist organization. Unfortunately, Hồ seemed premature in his desire for an anti-French movement because the arrest led to little response.

While in China, Hồ participated in several communist committees to organize Vietnamese youth. These later became united into the Communist Party of Indochina. Hồ sent a group of Vietnamese to the Nationalist Military Academy in Guangzhou to conduct training on armed uprisings.

Chinese Civil War detour

In order to better understand Hồ’s time in China, it is important to understand the political situation.

In 1911 Sun Yat-sen led a Revolution which ended the monarchy. He served as the first Provisional President of the Republic of China and moved the provisional government to Nanjing.

Yuan Shikai was elected for four years as the second Provisional President and led the Beiyang Army. He tried to restore the monarchy with himself as the new emperor but abdicated after 83 days. The country split into regions ruled by over a dozen warlords who would rapidly shift allegiances, known as cliques.

In response, Sun established a military junta (government by the military) in Guangzhou province (which contains the large cities of the Pearl River Delta: Hong Kong, Macau and Guangzhou). His junta apposed the warlords and the Beiyang government. In 1919 he formed the political party Kuomintang (KMT). The Chinese Communist Party formed in 1921, who positioned themselves as a KMT ally that later became a political rival.

Sun Yat-sen founded modern China. He is known for being both the first provisional president of present-day Republic of China (Taiwan) and a forerunner of the revolution of the People's Republic of China.

The KMT, also known as the Nationalists, were very open about ideology and accepted communists into their party under Sun’s leadership. He put more attention into the fight against foreign imperialism over ideology. Western countries rejected Sun’s government, so he sought aid from the Soviet Union. The Comintern instructed communists to join the KMT but keep their communist affiliation.

Sun had a good relationship with the Soviet Union and even received help from the Comintern and met Lenin. Both Sun and Lenin had flattering words to say about each other. Sun sent representatives to study with the Red Army. In return, the Soviets sent representatives to help organize the KMT. This alliance between the Soviet Union and the KMT became known as the First United Front.

Sun sent Chiang Kai-shek to Moscow in 1923 to study the political and military system of the Soviet Union for three months. Chiang met Leon Trotsky as well as other Soviet leaders. In 1924, Chiang returned to China and Sun appointed him to the position of Commandant of the Whampoa Military Academy where he would develop substantial influence over the National Revolutionary Army (NRA). Before long, Chiang submitted his resignation due to growing ideological differences, but Sun talked Chiang into staying.

Sun died in 1925. Powerful men started competing for Sun’s position, with men killing and arresting each other in a Machiavellian free for all. Chiang emerged as one of the stronger candidates for the leadership of the KMT. At this time, Communists only consisted of around 3% of the KMT but were growing fast and later outnumbered the KMT.

In March 1926, the Communists made an apparent attempt to kill or arrest Chiang. In response, Chiang organized the Canton coup, which purged communist elements from within the KMT around Guangzhou. Chiang declared martial law and placed the Communists under arrest. The Soviets were still unaware of the Communist purge as they tried to show solidarity with the KMT. They sent support in the form of teaching and munitions to maintain Soviet influence over the KMT to help Chiang secure his Northern Expedition with the goal to unite the country under one government. The Northern Expedition helped Chiang secure Beijing and Manchuria and also helped the KMT become recognized internationally.

Chiang found himself distrustful of Communist intentions, believing them responsible for the attempt to remove him from power. In April of 1927 Chiang’s army conducted a purge of thousands of suspected communists in Shanghai in what would become known as the “White Terror”. Left wing members of the KMT followed suit and joined their right-wing brothers in expelling communists, officially ending the First United Front. After this initial purge, over 300,000 suspected communists were killed across China in anti-communist suppression campaigns. In August, Mao Zedong led the Communists in an uprising in Wuhan, which led to the creation of the Red Army. The Communists later went to Guangdong province and were defeated. They fled to rural mountainous areas and set up Soviet republics.

In January of 1928, left wing KMT political rival, Wang Jingwei went into exile leaving Chiang the uncontested Commander and Chief. Chiang began integrating the armies of allied Warlords into the NRA.

Competing warlords created a coalition from March 1929 to November 1930 to fight Chiang in the Central Plains War. When the war concluded, Chiang’s attention once again returned to the Communists. Between November 1930 and June 1931, he began five encirclement campaigns against the Communists. Not much happened in the first three campaigns and the fourth campaign ended prematurely due to the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. The fifth encirclement finally sent the Communists on a “long march”. In 1934, more than 100,000 communists travelled west and then north over 370 days and more than 9,000 kilometers. Only 8,000 communists made it to Shaanxi province.

After years of losses, several NRA generals, led by Chiang's allied commander Zhang Xueliang, kidnapped Chiang for two weeks and forced him to make peace with the Communists. This became known as the Xian incident. Chiang and the generals formed a "Second United Front" with the Communists against Japan. After releasing Chiang and returning to Nanjing with him, Chiang placed Zhang under house arrest, and the generals who assisted him were executed. The Second United Front had a tenuous commitment by Chiang, but Chiang remained true to his word and upheld the alliance. He now directed 100% of his attention to the Japanese threat. The Communist alliance would survive until the defeat of the Japanese in 1945, when the Chinese Civil War would resume.

Marriage

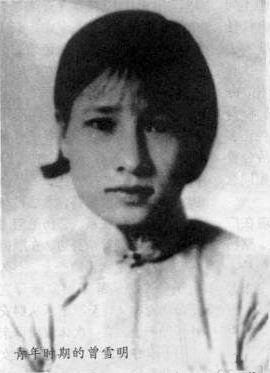

Hồ‘s remained in China during the early days of the Chinese Civil War. While there, Hồ cohabited with Zeng Xueming (Tăng Tuyết Minh), a Chinese woman 15 years his junior. The youngest daughter of a concubine, Zeng had a difficult life. Her father’s death forced her out of her family home at the age of 10. At 20, she graduated from a school in Guangzhou to become a midwife.

Mutual Vietnamese communist friend, Lâm Đức Thụ introduced Hồ to Zeng, whom Hồ wed on October 18, 1926. To the delight of Hồ, Zeng became pregnant shortly after, but she opted to abort the child for fear Hồ would leave China soon without leaving any support for the child. While some suggest Hồ had a political marriage, Hồ reportedly told his friends, "I will get married despite your disapproval because I need a woman to teach me the language and keep house."

Hồ left China after Chiang started purging communists in April 1927. The couple stayed married, but would not meet again. In 1945, Hồ admitted to journalist Harold Isaacs that he felt lonely, had no family, had nothing, but once had a wife.

After World War II, Hồ tried unsuccessfully to find Zeng through the Chinese Communist Party and the Vietnamese Diplomatic Agency in China. Members of the Politburo and Le Duan objected to this marriage because Hồ’s celibacy had become part of his myth. A cult of personality, perpetuated by the North Vietnamese government, had formed around Hồ. He sacrificed his family to marry the cause of independence. As his myth grew, Hồ began to repeatedly state that he had no wife and would not marry until Vietnam achieved victory and reunification.

This narrative likely resonated in the minds of villagers who still kept the Confucius values, which include filial piety. They would have understood Hồ’s sacrifice for the country. At that time, a man had the duty to maintain a natural heir for the ancestor cult. This must have weighed on the mind of Hồ because none of his siblings had children either, meaning no one remained to maintain the ancestor rituals.

In May of 1950, Zeng learned Hồ had become president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and sent him an unanswered message. In 1954 she sent a second letter, which also remained unanswered. Chinese government officials instructed her to cease her efforts to reach Hồ, implying that in exchange, they would offer to take care of her financial needs.

Later Zeng would admit that she was "not sure if this was a real form of marriage" because they had lived together to disguise their political activities.

French author Daniel Hémery, found letters from Hồ to Zeng in the French colonial archive, however, Chu Đức Tính, Director of the Hồ Chí Minh Museum denied them when he said, "this is a hypothesis that is more fiction than not" and "the facts have proven that it is not true."

The official government statement seems to neither confirm, nor deny Hồ’s marriage, but obviously they would prefer to keep the cult of personality intact. In May 1991, the Vietnamese newspaper “Tuổi Trẻ” fired editor-in-chief Vũ Kim Hạnh after the newspaper published a story about Hồ's marriage.

Personally, I like the idea of the marriage between Hồ and Zeng. It adds some humanity to realize that his struggle for the independence of Vietnam came at a personal cost. It seems obvious that Hồ cared for Zeng, but circumstances drove them apart. Even in the initial days after he became the mythical leader of Vietnam, he still searched for her. He admitted, his life had become lonely without a family or a wife. Unfortunately, he couldn’t stay married to her because he had already married the cause of independence. It is so tragic. That seems like such a better story than the official narrative.

On the Run

Due to Chiang Kai-shek's persecution of communist revolutionaries, Hồ left Guangzhou and fled to the Soviet Union through the Gobi Desert. Along the way, Hồ contracted tuberculosis and recovered in Crimea during the summer of 1927. In November he went to Paris. The following month, he went to Brussels, Belgium to attend a meeting of the General Assembly of the Anti-Imperialist League.

In the fall of 1928, Hồ spent several months in the Thailand village of Nachok, disguised as a bald monk, under the alias Tau Chin, to train overseas Vietnamese revolutionary tactics and write for a revolutionary newspaper. While there, according to Pierre Brocheux, he sent a letter to Zeng saying, "Although we have been separated for almost a year, our feelings for each other do not have to be said to be felt.” He left the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand) at the end of 1929 and returned to Hong Kong in early 1930.

Comintern instructed Hồ to resolve the conflicts between the competing communist organizations he set up in 1925. He united the three Indochina communist organizations into a single organization named the "Communist Party of Indochina", which became the "Workers' Party of Vietnam" and again changed the name to the "Communist Party of Vietnam". A failed uprising directed by the Communist Party of Vietnam resulted in the banning of the organization, along with orders to execute Hồ.

By March 1930, Hồ returned to Siam for a short time before returning to China under the pseudonym Sung Man Cho. In Hong Kong, government authorities arrested Hồ with the intention of handing him over to the French colonial authorities who sought to deport him to Indochina. His British lawyer Francis Henry Loseby, successfully contested the deportation. To circumvent a French extradition treaty, the local French newspaper reported that Hồ died in August of 1932. The British released Hồ in December of 1932 and, disguised as a Chinese scholar, embarked on a ship back the Soviet Union to study at the Lenin International School.

Accusations of being a traitor

While in Moscow attending yet another meeting of the Comintern, the Overseas Leadership of the Communist Party of Indochina wrote to the Comintern stating the negligence of Hồ led to the arrest of more than 100 members of the Vietnam Revolutionary Youth Association. They went on to say, Hồ knew that his friend Lâm Đức Thụ had been a traitor and continued to use Thụ anyway.

In addition, words Hồ said about nationalism in 1924 came back to bite him. Hồ refused to condemn landholders in Vietnam, instead claiming the French colonial system to be the true enemy. This led to the accusation of him not being “in line with class struggle”. Comintern forced Hồ to stay in the Soviet Union to deal with the allegations as well as explain why the Hong Kong authorities released him in 1932. Comintern authorities released him several years later, in 1938, due to lack of evidence of traitorous intentions. He returned to his work as a Comintern agent.

Return to China / Working with the OSS

In 1938, Hồ returned to China under the alias Hồ Quang as a Major in the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. He returned to his work as the principal Comintern agent overseeing Asian affairs. He worked in the office in Guilin, before moving to Guiyang, Kunming, and finally to Dien An, the headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese Red Army during the winter of 1938 to early 1939.

Hồ and his lieutenants, Võ Nguyên Giáp and Phạm Văn Đồng, returned to Japanese-occupied Vietnam in 1940, following France’s defeat by Germany, to lead the Việt Minh independence movement who were gathering in Cao Bằng (Northeast Vietnam). Hồ and his team managed a Việt Minh guerrilla force of 10,000. During this time, he led training for the Việt Minh and worked closely with the United States Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which later became the CIA, to drive the Japanese out of Vietnam and China. In May 1941, Hồ presided over the 8th Conference of the Vietnamese Communist Party Central Committee in Cao Bằng.

Over his lifetime, Hồ Chí Minh used many aliases. Estimates range from 50-200 different aliases, but I found the range of 160-170 different aliases most convincing. In August 1942, he took the name Hồ Chí Minh and went to China to support their struggle against the Japanese. The name Hồ Chí Minh became symbolic of a larger myth. Once that name became famous, it became his permanent name.

While in China, local authorities arrested Hồ a few weeks later and transferred him from prison to prison over the next year. In October of 1943, the Việt Minh finally received a letter confirming Hồ survived. The Việt Minh asked their OSS friends for help getting Hồ released. The OSS contacted the U.S. State Department which pressured Chiang Kai-shek’s government to release Hồ. In September 1943, China released Hồ.

In March 1945, Hồ Chí Minh met with American Lieutenant General Chennault in Kunming, China. Chennault thanked the Việt Minh for their help against the Japanese and said the U.S. would provide whatever aid they could. Hồ saw this as proof that the U.S. supported the Việt Minh and he began to work closer with the OSS in operations in Vietnam against the Japanese.

In April 1945, Hồ met with OSS agent, Archimedes Patti, and offered to provide intelligence, asking only for "a line of communication" between the Việt Minh and the Allies. The OSS agreed and dispatched a military team to train his troops.

According to Paul Helliwell, former OSS official and CIA officer, on Walter Cronkite’s TV show 20th Century, the OSS became hesitant to supply the Việt Minh with American weapons because Hồ Chí Minh refused to deny that the weapons would be used after the war to fight the French.

“When he [Hồ] came up and asked for arms, certain questions were usually asked and one question that I asked him, and I asked him every time, was ‘who is he going to shoot?’ and he said ‘he was gonna shoot Japanese’, which was fine. We would ask the question ‘What about the French?’ …and the give the devil his due, he would never commit that he would not use the arms against the French. At some point, had he made that commitment, he possibly might have gotten more arms than he did.”

The arms sent to Indochina to resist the Japanese were mostly sent to the French. The Vietnamese were only able to get their hands on the occasional shipment of American weapons and captured Japanese weapons during this time.

In July 1945, Hồ became seriously ill and thought he would not survive. A small OSS unit parachuted into Vietnam behind Japanese lines to assist the Việt Minh and encountered Hồ suffering from severe malaria. The OSS communicated with the U.S. military headquarters in China, requesting urgent medical supplies. After two weeks, a military doctor named Paul Hogland arrived. The Americans remained for two months, saving his life.

I wonder if, in hindsight, any of these OSS officers might have regretted their aid or medical treatment during this time. Did Paul Hogland later regret his actions had he known how influential Hồ would become after the war?

In the next section, I will discuss Hồ’s rise to power following the defeat of the Japanese Army.

Originally, I had planned on this series about the life of Hồ Chí Minh being a three-part series. I quickly found that part three became way too long for one section and decided to split that section into two parts.

The first part will contain the early days starting with the August Revolution and discuss the first Indochina war, where a guerilla war erupts with a bunch of skinny farmers armed mostly with hand-made muskets and Molotov cocktails. Hồ Chí Minh secured arms from the Soviets and Chinese and superior battlefield tactics of Võ Nguyên Giáp caused the Vietnamese to defeat their former colonial rulers.

The next part will contain the struggle to maintain independence as Vietnam enters the second Indochina war and goes head-to-head with the most powerful military in the world.

Stay Tuned!

Further resources:

The YouTube series by fellow Substack author Paul Hesse, who writes The Chinese Revolution, has been incredibly helpful for putting events into a larger context. If you want to better understand this era, which is sadly not yet integrated into most Western history classes, you should check him out. Not only does it help give context to what has happened to form modern day China, it gives larger context to the political situation that impacts the entire world today.

He led a very convoluted life, so many aliases, I wonder how he remembered so many names, and whether he came across people who knew him by a previous name? I had no idea that Vietnam has such a strong connection to Russia and China as you have mentioned in this series of posts. Of course with them all being Communists I get that they had similar views. I do get a bit lost at times, but I am sure others connect the dots better then me.

Fascinating