Many Westerners think Vietnam’s problems went away after the American War. Independence was only the first obstacle. After the U.S. left, Vietnam still needed to secure its Western borders from a genocidal dictator and make a stand against an aggressive big brother to the north.

By the mid-1980's, it was clear that the communist economic system was failing internationally and that the Soviet Union would no longer be able to support its client states. Each needed to figure out how to survive on their own. Generally the European client states dissolved and became capitalist democracies; socialist countries in East Asia followed the Chinese lead, transitioning from a centrally planned socialist model into a decentralized liberal economic model. The phrase Đổi Mới, meaning “renovation”, was the name given to this process of Vietnamese economic liberalization. This is the story of Vietnam’s transition.

With hyperinflation spiraling out of control, the initial decade after independence was extremely challenging. In 1981, inflation rose 100% year over year. This marked the onset of inflation doubling every year; 100%, then 200%, then 400%, and so on. At one point, Vietnam had among the highest annual inflation rates in the world – well over 700%.

Many people didn’t seem to notice the severity of the problem because most were poor farmers. No one had any money because they felt compelled to spend it quickly upon receipt, because waiting even a few months could result in losing up to a third or half of its value.

Life before Đổi Mới

When I talk to farmers who remember that time, most say they never had money. The country reverted to a type of barter system in which the major staples (e.g. rice) were immediately purchased following the sale of crops, and everything else was made at home.

The total GDP of Vietnam was less than U.S. $100 per person per year. Much of this was concentrated among an elite class at the top. The common people of the countryside made much less. Typically, farmers earned just enough to afford a few bags of rice and some household essentials necessary for daily life. They learned resourcefulness and to make do with what they had.

If a person needed new clothes, they might buy large pieces of fabric and sew clothes at home. Many families had mechanical Singer sewing machine replicas with a foot peddle they pumped to move the needle, like the one my U.S. grandmother used in the 1930’s.

When families desired meat, they often hunted. The chickens and pigs they raised were typically saved for special family feasts. Meat was more of a special treat than something eaten at every meal; the skill lay in stretching the meat across as many meals as possible. In the city, street food vendors displayed remarkable knife skills, slicing meat so finely to give the appearance of a significant portion of meat in the soup or in a bánh mì, when in reality, there was very little. A whole bowl of soup, costing only around ₫2,000 (roughly U.S. $0.50 in today’s money, a significant sum for the Vietnamese in the mid 1990s) might contain just a few grams of meat, artfully arranged to appear more substantial, with noodles and vegetables providing the bulk of the dish.

The search for fresh meat would mean a trip out to the fields of the countryside to find crabs or fish in the canals or fat rats who were enjoying the farmers produce. Eating rat sounds a little disgusting to Western ears, but it should be noted that these are farm rats, which don’t have the diseases of city rats. They were typically fat from eating a lot of fruit, which also gave the meat a bit of sweetness, and tasted like pork. They also come with nice little skewers in the form of their tiny little leg bones.

I get a bit sad when I think about the ecological diversity that was mostly destroyed during that time. People were hungry and they ate everything. There wasn’t an animal alive that was off-limits with a hungry wife and kids at home.

Interestingly, throughout this time, the population rose steadily. Many people think that war and famine decrease a population, but in Vietnam, this wasn’t the case. When there is no birth control and nothing to watch on TV (if you were rich enough to own a TV), there’s only one form of home entertainment.

Back then, a woman living out in the country didn’t go to the hospital to have a baby. It was too difficult to get there by bicycle or ox cart, and no one had the money to pay for the hospital, so most people had their children at home. Though there were very experienced midwives, some mothers and babies died. I have quite a few friends born during this time and some confirm they were born at home. I’ve heard several stories of someone’s aunt or first wife who died giving birth.

Following food and medical needs, transportation becomes the priority.

When people think of Vietnam today, they often think of motorbikes, but few people had motorbikes back then. Of those who did, many didn’t have money for gas. People either cycled or crowded into vehicles that remained after the wars. The larger cities had some buses, to transport people around the city, and there was a network of chicken buses, which is a multi-use bus to carry passengers and cargo (oftentimes chickens and other animals) around the country, but many people never had the need to leave the countryside. The most common type of transportation was from a century earlier – a worn-down pair of shoes.

Honda imported 20,000 Honda Cub and Honda 67 motorbikes in 1967, the first mass-produced motorbike exported to Vietnam for civilians. There were a few of these motorbikes in the larger cities, but only rich people could afford them. They were well maintained and usually stacked with items for delivery. The shiny new paint of the 1967 models had long since worn down to primer by the mid-1980’s and run far longer than the intended lifespan of the engine. Many of the 67 motorbikes would often face the metamorphosis of turning into the Frankenstein’s monster of vehicles we sometimes see today, with the front part welded on to a boxy rear chassis which were used to transport people, livestock, or goods.

The problems with a centrally planned economy

Economies that experiment with the centrally planned model eventually run into failures. The problem is that the larger a system becomes, the less information travels up the chain of command. When you don’t know the conditions of local markets, it is nearly impossible to predict which goods may be in demand the following year. Maybe certain crops don’t grow well in certain areas. Maybe a local market has an oversupply of a given good, and transportation prices or long transit time to other markets cause the item to be too expensive or get damaged in transit. In these cases, it is better to let people at the production level determine the correct mix of products to produce, given the parameters of the local market.

The person producing a product knows much more about the intricacies of their product more than any committee and have the ability maximize production. This increased efficiency adds to the business owner’s profits. As profits accumulate, other businesses will notice this product is highly profitable, and that will encourage competition from other businesses also wishing to maximize their profit. This increased competition will drive prices down until all products are produced in the most efficient way possible for the lowest possible price for the benefit of all consumers of this product.

When a central committee determines a product quota, inefficiencies tend to accumulate in the system resulting in a major drop in total production. This is due to the complexity of an economy, which involves numerous factors to consider.

In a centrally planned system, everyone receives the same pay for meeting a quota, leaving people who work beyond the minimum quota unrewarded for their extra effort. There is a cost to the extra effort needed to obtain higher production. A person requires more resources such as food or more frequent breaks. The only logical solution is to meet the bare minimum quota to conserve resources. This naturally drives production to the minimum required levels.

If there is an oversupply one year of a substitute good, it may cause the demand for all other similar goods to go down. The next year, that substitute good may return to normal production levels, but the other goods have had their quotas reduced, thus creating a shortage of an important good. Since there is no benefit to the worker for increasing production of a product in high demand, the products people need are always less than total demand and there is an oversupply of products no one really wants.

Đổi Mới reforms

The 6th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam met in December 1986 to discuss their response to supply shortages from the Soviet Union. These shortages were caused by a 1985 rapid loss of the Soviet Union’s hard currency reserves due to falling oil prices as Saudi Arabia oil increased production. Because oil is a large part of the Russian economy, these price drops quickly sucked huge amounts of money out of the economy. The initial cuts were in foreign aid to countries within the Communist sphere, including Vietnam.

This put stress on the entire centrally planned Soviet economy causing the need for the reforms of Perestroika and Glasnost. Perestroika introduced a system of economic reforms to Soviet economic markets. Glasnost opened up transparency among government agencies with the hopes of increasing the flow of information that was lost in a centrally planned system. These reforms reintroduced capitalistic market forces to the economy in an attempt to end the economic stagnation of the previous couple decades.

Soviet market reforms were in the front of everyone’s mind as the National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam met. The Vietnamese could no longer rely on foreign aid from their largest supporter, The Soviet Union. They were on their own and needed to act quickly. Inflation was out of control and the economy had been steadily shrinking since 1975.

They needed to move from a centrally planned system into a socialist-oriented market economy by expanding their market beyond the Communist States. To do this, they would need to increase productivity and competitiveness in a global market. This was further complicated by the deep suffering of many Vietnamese after decades of war, followed by ostracism from the U.S. global order.

Between 1975 and 1994, the U.S. imposed an embargo upon Vietnam. This meant zero foreign investment from U.S. banks or access to U.S. markets, the largest importer of manufactured goods in the world. As access to communist markets dried up, Vietnam found itself with increasingly fewer trade options.

Vietnam implemented several reforms at the same time to liberalize the economy, attract foreign investment, and promote market-oriented policies. Central to these reforms was the decentralization of economic decision-making, allowing local governments and enterprises greater autonomy to respond to market dynamics. They removed price controls to allow supply and demand to decide prices, thus fostering efficiency and investment.

In addition to decentralizing the economy, they created a system of private ownership. Mechanisms were implemented to allow individuals to own private businesses which compete alongside state-owned enterprises (SOEs). These SOEs were restructured so they could operate more efficiently. SOEs were a good compromise between the centrally planned model and a fully capitalist model because an SOE can guide the private sector and provide economic infrastructure.

A few examples of SOEs include:

PetroVietnam (the oil and gas monopoly)

Vietnam Posts and Telecommunications Group (postal and telecommunications infrastructure that private cell phone companies can use)

Vietnam Electricity

Vietnam National Cement Company (manage cement manufacturing)

Vietnam Airlines (the flagship Vietnamese airline provides a price ceiling for other airlines to compete against)

Vietnam actively sought foreign investment by creating special economic zones and offering incentives to attract capital, technology, and expertise. The capital investments created jobs and, long term, Vietnam would be the fortunate beneficiary of skills transfer, allowing Vietnam to become globally competitive in manufacturing markets after several decades of experience. In addition to direct foreign investment, they would need to create a stock market to allow for passive foreign investment. Vietnam would provide land and labor for production while their partner companies would provide investment and manufacturing experience.

Agricultural reforms abolished collective farming, empowering farmers to operate independently and adopt modern techniques, thereby boosting agricultural productivity. By decentralizing farming, the more talented farmers would gain higher profits while less talented farmers would go out of business and sell their land to the better farmers to further increase profitability. Farmers were allowed to pick the best mix of crops which would thrive on their land and change out crops to maximize production of each farm. Profit could be invested into better agricultural methods to again increase productivity, creating an upward spiral of innovation. Agricultural reforms were crucial, ending collectivization and empowering farmers to adopt more efficient methods. Today, Vietnam is the number three global exporter of rice, right behind India and Thailand.

Industrialization was prioritized, with private ownership and foreign investment encouraging modernizing industries and diversifying the economy beyond agriculture. Vietnam realized that if they were to compete, they needed to create more value-added services. This could only happen with increased industrialization. They would take the lead of their Chinese neighbors to the north, following their example of opening special economic zones and joining international trade agreements. This attracted investors with the experience necessary to set up factories.

As in other developing countries, Vietnam started with textiles and gradually added higher value-added products such as electronics and footwear. Trade liberalization reduced tariffs and barriers, facilitating Vietnam's integration into the global economy. As Vietnam’s openness became apparent, the U.S. reopened relations and encouraged membership into global trade organizations, including the World Bank starting in 1993. The World Bank is important for financing infrastructure projects, and it gives grants to achieve objectives of reducing poverty as well as improving education. This gave Vietnam the investment they needed to improve infrastructure for companies to come to Vietnam.

Implementing Đổi Mới

The first few years were tough. Even though inflation dropped to less than a third of its 1986 level, it remained out of control until 1989. The first step was a stabilization of the currency.

Easing price controls, raising interest rates, limiting subsidies to inefficient state-owned enterprises and devaluing Vietnam’s currency were all necessary. This was incredibly difficult because everything needed to happen at once. To improve efficiency, inefficient government jobs were slashed, causing many people to lose their jobs. According to the World Bank, the total number of Vietnam’s state-owned businesses dropped from 12,000 during the early 1990’s to as low as 1,000 in 2010.

By 1989, much of the legal infrastructure was in place and Vietnam started to attract interest. In 1993, Senators John McCain (a former US Navy pilot who survived six years of torture by the North Vietnamese during the American war, in what many called the Hanoi Hilton, Hỏa Lò Prison) and John Kerry (a former US Navy officer who also served in the war) made their historic visit to Vietnam to dispel much of the bad blood between the U.S. and Vietnam. Six months later, in January of 1994, the Kerry-McCain sponsored Senate resolution urged the President to lift the embargo. It passed 62-38, and the following month, President Clinton dropped the embargo.

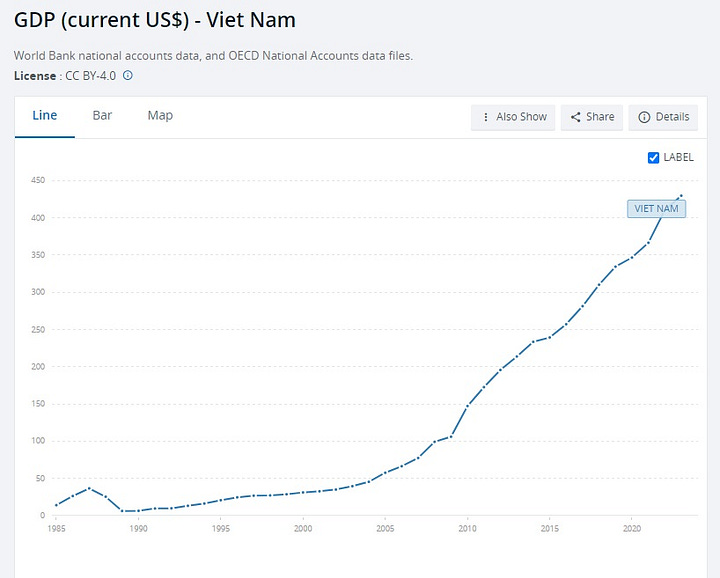

Growth suffered an initial setback as the economy retooled and initial growth started slowly. After the initial shocks, total GDP dropped to a little over U.S. $6 billion. It took the GDP nearly a decade to return to pre-reform levels. It doesn’t seem like it when you are looking at a linear chart, but the growth rate of the Vietnamese economy grew exponentially since 1990 with a 5-9.5% growth rate each year. The growth rate really seemed to pick up in 2005 when the economy rose from approximately U.S. $50 Billion to U.S. $250 Billion by 2015.

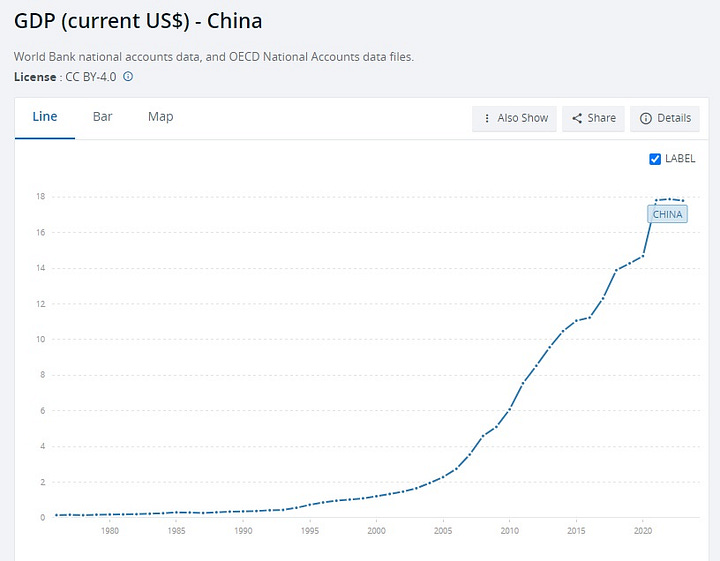

Although the reforms of Vietnam were more than a decade behind China’s, the multiples are nearly the same. Since 1989, Vietnam’s economy has grown by 65 times; the Chinese economy has grown by approximately 60 times. China’s growth appears to have slowed over the last few years, while Vietnam’s growth rate shows no sign of stopping in the near future.

Many people talk about the “Chinese Economic Miracle”, apparently without realizing that the Vietnamese Economic Miracle is just as amazing. Vietnam is still in the Chinese economic wake with approximately 10% of the Chinese population and China’s decade-plus economic head start. If Vietnam continues to follow their current course, the economy will likely end up with the same GDP per capita as China in a decade or two.

China has reached the end of their demographic dividend, with large bands of their population already in their 50’s and total population growth on the decline. Vietnam is in a different situation. They only started growing in the late 1980’s, and their population growth only started to slow in 1995. This puts Vietnam in that perfect sweet spot for growth, with a large population of workers from age 30-50 who can pump economic production into high gear. Vietnam still appears to have a decade or two until they reach the economic and demographic challenges China is dealing with today.

The Effects of Đổi Mới

There are plenty of stories I could talk about to drive home the importance of the economic reforms to Vietnamese.

The amazing freedom a Vietnamese person obtains when they are finally able to own their own farm or home.

How the ability to get a job and save some money transformed the lives of several generations.

How the cell phone completely changed the way Vietnamese do business.

Despite these interesting stories that could apply to any of the former Soviet satellites, nothing is quite as unique or iconic in the minds of most Vietnamese as owning a motorbike.

Sometimes these articles can get into some technical jargon and they lose the personal message. In this case, I really wanted to focus on the increased standard of living of Vietnamese people. Nothing quite shows the increase in quality of life than talking about a tool which has become so common, it is now synonymous with Vietnam.

I mentioned before that in 1967 Honda imported 20,000 Cubs into Vietnam, nearly 90% of all the motorcycles used in Vietnam. In 1998, just a decade after Đổi Mới, Honda built their first factory in Vietnam. It started with an annual capacity of 400,000 vehicles, the majority of which were Super Cubs. By 2011, Honda had built 10 million motorbikes for Vietnam. Five years later, they doubled that production number to 20 million motorbikes. Honda has subsequently opened two more factories and continues to build 2.5 million motorbikes a year in Vietnam. There are now over 48 million motorbikes in Vietnam, nearly one motorbike for every adult working age person in Vietnam, 73% of which are Hondas.

To tell what a motorbike means to Vietnam, I must briefly talk about the Honda Dream. The Dreams were the upgrade to the Cub, doubling the normal Cub engine size. These things are work horses. Although the Wikipedia page says Honda is still producing that model, I am told by dealers that it is no longer available in Vietnam. The Dream is still loved by nearly every old man and old delivery driver around Vietnam.

These motorbikes were worked to death. I am told that the name Dream became synonymous with the fantasy the motorbike represented. The thought of owning a motorbike was so far out of reach for most Vietnamese that when this motorbike was introduced in the early 1990’s, many people who were finally able to get some money to buy a motorbike felt like they were dreaming to have such luxury. Look around when you get here, many of these bikes are still on the road.

When you hear how this iconic motorbike is revered by some old men, you can get an idea of what this motorbike meant to people who had nothing.

A motorbike represented personal freedom. People left their hometowns to go on vacation someplace very far away (for example, 20km to the beach).

It also represented economic freedom. Owning this motorbike meant someone could suddenly start selling their goods directly in the big city instead of selling to the local co-ops around their town.

The motorbike represented an end of subsistence living and the beginning of getting ahead in life.

Rural Vietnamese life immediately changed for the better. With the introduction of the motorbike, it finally seemed that Vietnam was waking up from the nightmare of poverty it endured for the last couple centuries. It is no wonder Vietnamese love their motorbikes and has such a powerful motorbike culture.

Vietnam was able to successfully transcend the challenges they faced as the Soviet Union dissolved. Through their system of Đổi Mới, they were effectively able to transition from a centrally planned socialist model into a decentralized liberal economic model. They were able to meet the initial challenge of hyper-inflation followed by the complexities of transitioning an entire economy within a few years. Currently, Vietnam ranks as the 35th largest economy in the world and has a growth rate which is only rivalled by the “Chinese economic miracle”. Vietnam isn’t done with their growth story and I expect to hear more about the economy of this emerging market as they take their rightful place among the other powerful economies of East Asia.

References used while writing the article:

https://data.worldbank.org/

https://www.populationpyramid.net/

https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/VNM/vietnam-raising-millions-out-of-poverty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honda_Super_Cub#Super_Cub_line

https://global.honda/en/Cub/world/factories/vietnam/

https://www.thehonda67andcubfactory.com/

Do you accept civil disagreements?

If so, ...

Your positing of centrally planned economies versus liberalised economies strikes me as deeply flawed, and the basis for such a view are my readings of authors like the economists Ha-Joon Chang and Michael Hudson, and Alex Krainer. To summarise their arguments in a brief comment is virtually impossible, so I would only direct you to them.

My Sunday afternoon reading, I laughed when you mentioned the only form of entertainment, of course we all know what that would be… my husband, as I may have mentioned went to Vietnam several times for business. He worked for Fosters Brewing as the International Risk Manager, and when Fosters formed an alliance with the Vietnamese to make beer, he had to ensure that all risk taking in the factory was eliminated. He can’t remember the name of the beer that was manufactured, “Blue something” and it was the biggest selling beer in Vietnam. This would have been around the mid 1990’s. Another very informative read.