When most people think about the Opium Wars of the mid-19th century, they only think about the conflict between the British and the Chinese. In reality, the war’s influence stretched far beyond the borders with China and rippled throughout South East Asia.

In the case of Vietnam, it may have been a contributing factor leading to the defeat of the Vietnamese Empire by giving the French a foothold in the region. The effects of this war were long lasting and the impact is still felt to this day.

What were the Opium Wars?

The Opium Wars got started after the British took India (which included Pakistan) in 1764, when the British found that they were in control of an incredibly potent narcotic. Northern India (Pakistan) is a great place to grow opium poppies, but the British needed to find a market for it. There was the medical market in Europe, but do you really want a bunch of drug addicts in your back yard? The European market is only so large before you saturate the total market. The British needed to find a massive market far away from Europe who also happened to have a trade deficit with Europe. That was China.

Up until the Opium Wars, China was the king of manufacturing trade goods which Europeans couldn’t get enough of. Among these were the high quality Chinese ceramic pottery, silk cloth, tea and spices …to name a few. This caused a trade imbalance because there wasn’t any product the Europeans were making that the Chinese also wanted. The Chinese wanted silver because the Emperor had decided that taxes could only be paid in silver, creating massive demand for silver within China. This meant that the silver from Europe was migrating to China and Europe was running low on currency.

The British found a product that the Chinese wanted …and they REALLY wanted it. That was opium. Smoking opium was illegal, but the British got around that by bringing their products off the coast of China and letting local Chinese merchants handle the pick up of opium from the ships and handle the distribution. After a few years, it became clear it was becoming a big societal problem. There were opium dens popping up all over the port cities and even making its way to the Forbidden City. The Emperor had to do something, so he issued a decree banning any imports of opium into the country. In the early 19th century, the American’s also entered the opium business with less expensive, low quality, opium from Turkey, driving down the price.

The Chinese Emperor issued an edict, which didn’t do much to stop importation, but he was making it clear he was not going to tolerate opium much longer.

Opium has a harm. Opium is a poison, undermining our good customs and morality. Its use is prohibited by law. Now the commoner, Yang, dares to bring it into the Forbidden City. Indeed, he flouts the law! However, recently the purchasers, eaters, and consumers of opium have become numerous. Deceitful merchants buy and sell it to gain profit....If we confine our search for opium to the seaports, we fear the search will not be sufficiently thorough. We should also order the general commandant of the police and police- censors at the five gates to prohibit opium and to search for it at all gates. If they capture any violators, they should immediately punish them and should destroy the opium at once. As to Kwangtung (Guangdong) and Fukien (Fujian), the provinces from which opium comes, we order their viceroys, governors, and superintendents of the maritime customs to conduct a thorough search for opium, and cut off its supply.

The Chinese Emperor had trouble doing anything to the Europeans, so he turned his attention to the Chinese dealers and started sending his officials to arrest the Chinese dealers and confiscating their opium along with the British supply of opium in their warehouses in Canton (totaling 20,000 chests of opium, which is about 1,400 tons).

This was eating into the profits of the British, who were enjoying a reversal of the trade deficit of previous years which had the effect of sending seven million silver ounces flowing back to Britain coffers in just three short years. The British demanded that the Chinese pay for the confiscated opium and the Chinese refused. This meant the British would need to use more forceful negotiation tactics, so they declared war.

The First Opium war didn’t last long (1839-42). Even though the Chinese invented gunpowder, they mostly used it for fireworks and their guns sucked. The British had a much better technological advantage because they were constantly having wars, with the Spanish, French, American’s, all of their various colonial uprisings, etcetera. The early wars with the Spanish insured the British had the best Navy and the Napoleonic wars insured they had some decent artillery on their ships. The Chinese didn’t stand a chance. China was defeated and with the Treaty of Nanking, China ceded Hong Kong to Britain and opened several Chinese ports to foreign trade, without the interference of Chinese law upon the European merchants.

About a decade and a half later, the British wanted to renegotiate the treaty as they wanted to increase influence within China. They wanted official diplomatic embassies in Beijing along with the right to open up more trading cities. The Chinese refused and in 1856, it all came to a head when Chinese authorities boarded a Chinese-owned, but British-registered ship, the Arrow, in Canton (Guangzhou). The Chinese arrested the crew on suspicion of piracy and smuggling. Britain claimed this violated their extraterritorial rights and decided to send back the war ships.

This war was a little different than the previous war because this time, the British brought friends. The French and the American’s decided to join in, along with minor partners of Japan, Germany and Russia. They all wanted trade ports of their own. This war ended with the Treaty of Tientsin in 1860, which further opened China to foreign influence and legalized the opium trade. By the end, the Chinese empire was substantially weakened. This war didn’t end the dynasty, but it started the beginning of the end and the dynasty fell apart a little over 50 years later when a European type of Republic government overthrew the Dowager empress.

This YouTube Video gives a great lesson about the history of Opium in China.

What does any of this have to do with Vietnam?

The second Opium War was starting to wind down and the French were having trouble with Vietnam closing off to the French missionaries. In 1858, the French sent Naval ships to Cửa Hàn (present day Đà Nẵng). That went well, but the French were not able to make progress inland and they worried about a Vietnamese counterattack. The following year (1859), the French planned to go to Saigon to destroy Vietnamese army provisions so the Vietnamese couldn’t stage an effective counterattack.

Saigon was a much more defensible base of operations. It wasn’t long before the French had Saigon under their control and chose to relocate their base of operations to Saigon. The Opium War in China was coming to an end and many of the troops and ships were already in East Asia, so the French Navy was diverted to Saigon to begin the conquest of Cochinchina (South Vietnam). Initially Vietnam Emperor Tự Đức gave up three provinces in an 1862 treaty. By 1867, the French saw the potential in Vietnam and pushed for another three provinces to secure Cochinchina. After Cochinchina was secure, they started taking over the rest of Vietnam.

The Cambodian’s saw the writing on the wall and they were squeezed between the French and the Siamese. They asked the French if Cambodia could become a protectorate, which of course the French quickly agreed to. The French persuaded the Siamese to give three northern provinces, to expand the borders of Cambodia, and additionally took what became Laos from Siam in some hostile negotiations when the French Navy showed up near Bangkok to insist Siamese King Rama V cede these Siamese occupied lands to the French.

What about Opium in Vietnam?

The French allowed the free use of opium all over their colony. They did help the British win the second Opium War after all, so I guess the British talked them into letting them sell opium in a French colony. It probably wasn’t such a bad trade as the French did get access to several trading port cities in China as a result of the war, so maybe they figured they owed the British one here. Realistically, it was just a good source of taxable income, accounting for up to 20% of colonial revenues, and a way to control the populace. I read somewhere that the tax of opium was the only profitable aspect of French colonization in Indochina.

At first, the opium monopoly was granted to Wang Tai, a Cantonese Businessman, who processed the opium into smokable “chandoo”. He received a healthy commission for the sales infrastructure network he set up of licensed opium dens to sell British opium. By the 1870’s, he became the colonies first millionaire, but within a short couple decades, he found himself on the wrong side of the colonial government who felt they were taken advantage of.

Manufacturing of raw opium was nationalized at the Manufacture d’Opium at 74 rue Nationale (which is currently at 74 Hai Bà Trưng and operates as the upscale “The Refinery” group of upscale restaurants). Wang still worked with the French to distribute the opium, but now he was one of many trading houses.

According to Dr. Bernard who wrote De Toulon au Tonkin (in 1885), he mentioned that Wang Tai received an annual profit from his monopoly of several million francs annually. After the opium trade was nationalized, it netted the French government a respectable 8.6 million francs annually as of 1885.

By 1891, Wang Tai lost the last of his credibility, when it was revealed through two local newspapers that Wang Tai had received much of his business success due to a series of bribes, in exchange for government officials turning a blind eye to his smuggling operation. His good name may have been ruined, but the success of the family businesses continued for decades.

In 1905-10, the Yunnan railway was constructed, which opened up a supply line of opium from Yunnan province in southern China. The French combined the regional opium agencies into one and the Saigon manufacturing building, Manufacture d’Opium, expanded to take over the entire block. To encourage more opium consumption, the French developed a new fast burning variety of “chandoo” (Does this remind anyone else about the Crack epidemic in the U.S.?).

The French later sought to reduce the supply of raw opium further by switching suppliers to Persian and Turkish suppliers. After WWII, the French were no longer able to source their opium from the Middle East, so they encouraged more local production in upland Indochina in what would be called the “Golden Triangle”.

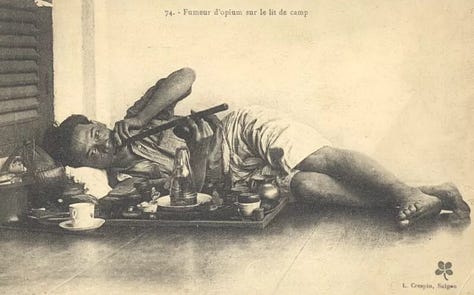

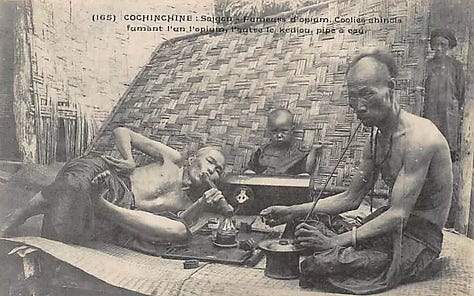

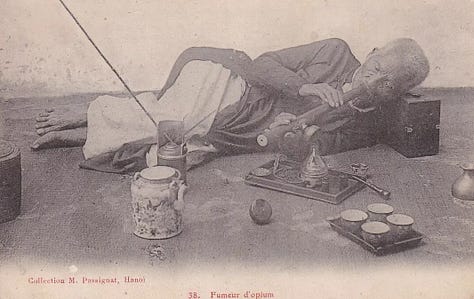

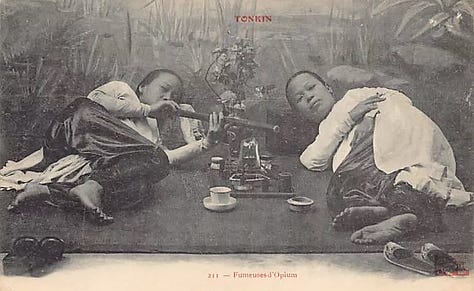

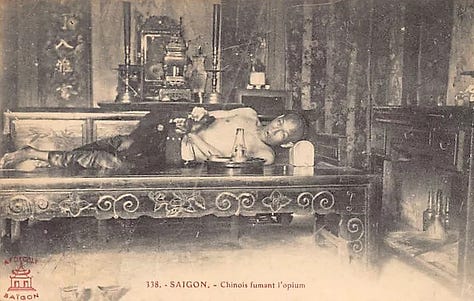

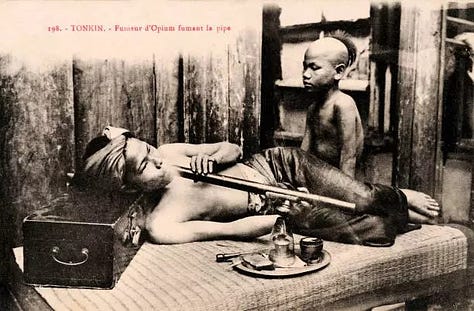

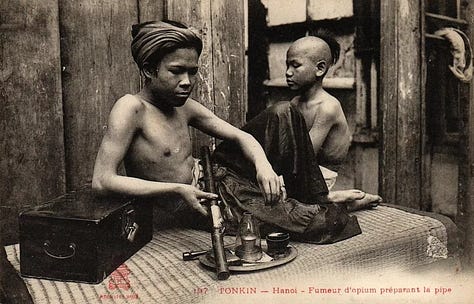

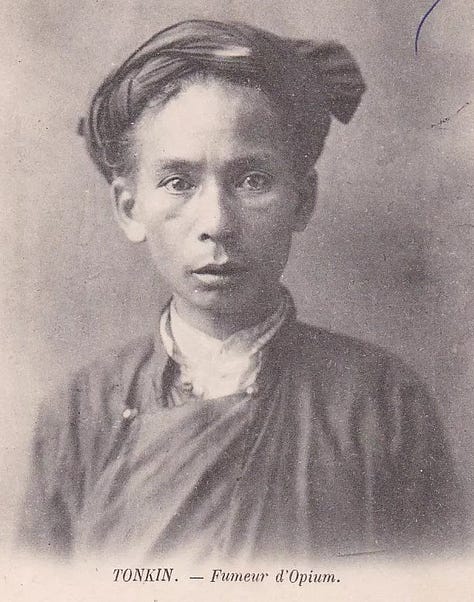

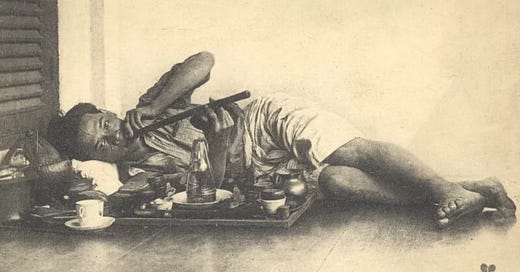

Opium dens sprung up in every major city in Vietnam, with Saigon being the manufacturing hub of the colony. At the turn of the century, opium use became such a common occurrence, that there were entire series of post cards issued about the practice. East Asian opium smoking became a meme in the minds of Westerners.

The opium den became associated with Chinese people and was thought of as a way for the Chinese to infect Westerners with their weak morals. Realistically, Americans were already cocaine and opium addicts through the use of patent medicine. Both civilizations enjoyed the use of opium, but Chinese preferred smoking it rather than drinking it in a liquid form or injecting it as Heroin. Some Westerners enjoyed smoking opium too and they may have visited the opium dens for a quick hit, but this would have been looked down upon as drinking or injecting were the civilized methods of opium consumption.

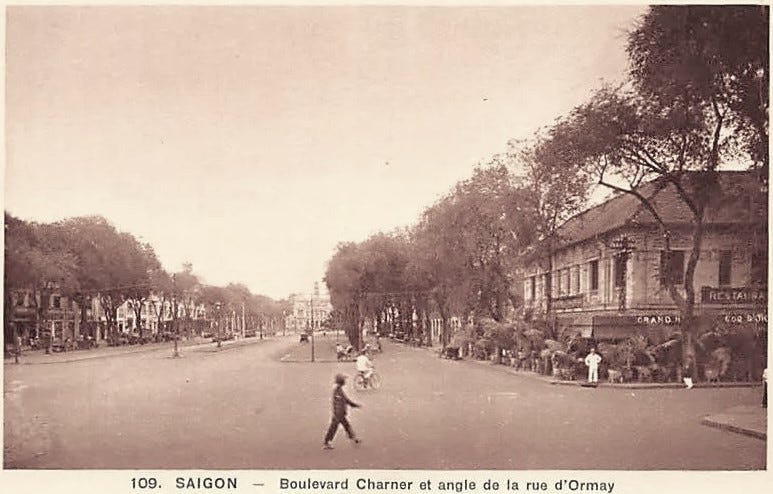

Graham Greene, the author of The Quiet American, was not ashamed to openly talk about his opium usage at the opium dens. When Greene was in Saigon from 1952-55, the opium dens were still functioning. He spoke very warmly about his experiences, enjoying the opium pipe with his girlfriend. One infamous street was the rue d’Ormay (currently Mạc Thị Bưởi) which was filled with opium dens until 1955. This was the street visited by Fowler in the book “The Quiet American” after Phương leaves Fowler for Pyle.

It was so common that by the time of the American / Vietnam war, the American soldiers would come in as clean cut young men and by the end of their tour, nearly half had tried some sort of opiate and nearly 20% became addicted.

It wasn’t until after Vietnam was reunited that Vietnam started to turn their attention to the opium epidemic. There have been campaigns to stop the use of drugs in Vietnam, without much success.

Deaths from drug use is still a problem in Vietnam today, with among the highest death rates in the world at 36 deaths per million between the ages of 15 and 64. The supply line is still largely supplied from the “Golden Triangle”, as the French set it up, which supplies all of the opium users needs from Cambodia, Laos and Thailand. If you want details, you can read this study about Vietnamese drug statistics. Currently, opium is highly illegal in Vietnam with sentences for the casual user ranging from 7 years to 20 years in prison, with more severe sentences for crimes such as trafficking ranging from a life sentence to the death penalty. Even with such harsh penalties, deaths from the harder drugs are still at high levels when compared to other countries.

As I was doing research on this subject, I found this article detailing a fascinating history of opium in Vietnam from the French Colonial era to this day. It gives a better history of the French Indochina opium production and has a few pictures of opium production sites and a map of the central opium factory in Saigon. It gives a bit more detail about actual locations in Saigon where opium was produced along with more details about its impact on Vietnam.

What an insidious situation. Who would have thought that this was still a common practice. Maybe I am being naive. Personally I have never understood the need or desire for anyone to take drugs and particularly today where you would have no idea where most of it has been produced. c’est la vie!

Maybe it would help curb the current drug problem in VN if they created a new set of postcards.

Any photographer wandering the streets of D1 or D3 in Saigon would find plenty of subjects, both Vietnamese and Westerner.