When a person thinks about Robert McNamara, US Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson from 1961-1968, it is hard not to feel strong emotions. Some call him the architect of the American War in Vietnam. Some call him a monster for the horror he participated in as the American managerial system was retrofitted from a system of manufacturing using modern management techniques to a system of total war (which is unrestricted war that not only targets soldiers, but the civilians who provide the resources for war). They took everything good and noble about American Capitalism and turned it into a weapon of war. …at least, that is what I thought.

I have conflicting feelings on the man. I did not come of age until well after the American War in Vietnam, so unlike many Boomers, my views on the war were based upon many of the anti-war movies of the 1980’s and 1990’s – Full Metal Jacket, Platoon, Born on the Fourth of July, Casualties of War, and even Rambo. Of course I thought of the war as a tragedy.

It was a difficult time and many people were trying to make sense of a tragic situation. When I saw the 2004 McNamara mea culpa film, The Fog of War, I was filled with conflicting emotions. The man oozed charisma in a sort of grandfatherly way, trying to impart his wisdom on a new generation as he explained the complexities of how to navigate the Cold War in the age of nuclear weapons. I found myself thinking, “How can I start to like such a monster?” It became clear there was so much nuance to the war that was never really addressed in the post war healing of the late 1970’s to early 1990’s.

The NY Times gave a brutal obituary when McNamara died, taking some quotes that I believe come from the movie in which McNamara held nothing back as he owned up to his mistakes during his orchestration of the American War in Vietnam. A couple of these quotes include:

“We burned to death 100,000 Japanese civilians in Tokyo — men, women and children,” Mr. McNamara recalled; some 900,000 Japanese civilians died in all. “LeMay said, ‘If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.’ And I think he’s right. He — and I’d say I — were behaving as war criminals.”

and

“What went wrong was a basic misunderstanding or misevaluation of the threat to our security represented by the North Vietnamese. It led President Eisenhower in 1954 to say that if Vietnam were lost, or if Laos and Vietnam were lost, the dominoes would fall.”

I freely admit that I was brainwashed by Hollywood into believing that none of the men who led the U.S. into war in Vietnam could ever be anything but monsters. McNamara changed this point of view as I realized a monster of my youth was really just an idealistic Alden Pyle.

Robert McNamara gave an interesting interview on CNN for an episode of a show called “Cold War” in June of 1996 that shed some light on events behind the scenes at the White House in the early days of the war in Vietnam. The quotes below originate from that interview.

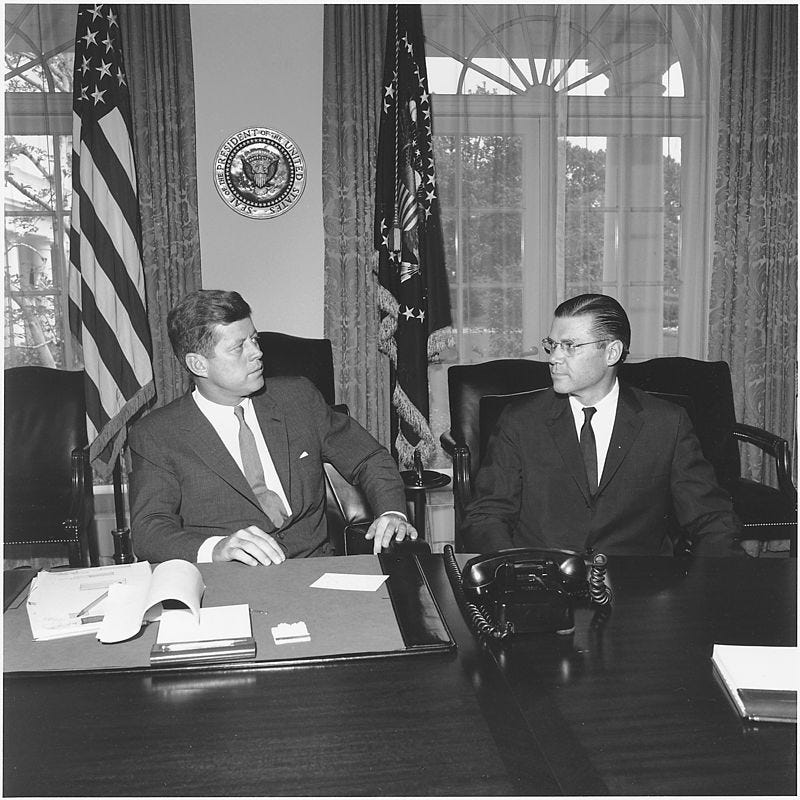

Kennedy handpicked McNamara to be part of his cabinet and it was decided McNamara would leave his job as the President of Ford to become the Secretary of Defense. This came at substantial cost to his family due to a large pay cut to take the job. The family agreed to the sacrifice because it seemed McNamara could make a change for good in the world.

The day prior to the inauguration, Eisenhower and Kennedy had a meeting with their respective cabinets. When asked why the U.S. became involved in Vietnam, McNamara referred to this meeting when he said:

[The domino theory] was the primary factor motivating the actions of both the Kennedy and the Johnson administrations, without any qualification. It was put forward by President Eisenhower in 1954, very succinctly: If the West loses control of Vietnam, the security of the West will be in danger. "The dominoes will fall," in Eisenhower's words. In a meeting between President Kennedy and President Eisenhower, on January 19, 1961 -- the day before President Kennedy's inauguration -- the only foreign policy issue fully discussed dealt with Southeast Asia. And there's even today some question as to exactly what Eisenhower said, but it's very clear that a minimum he said ... that if necessary, to prevent the loss of Laos, and by implication Vietnam, Eisenhower would be prepared for the U.S. to act unilaterally -- to intervene militarily.

And I think that this was fully accepted by President Kennedy and by those of us associated with him. And it was fully accepted by President Johnson when he succeeded as President. The loss of Vietnam would trigger the loss of Southeast Asia, and conceivably even the loss of India, and would strengthen the Chinese and the Soviet position across the world, weakening the security of Western Europe and weakening the security of North America. This was the way we viewed it; I'm not arguing [we viewed it] correctly -- don't misunderstand me -- but that is the way we viewed it. ...

Laos was in the front of Eisenhower’s mind because a little over a year prior to the Kennedy inauguration, the North Vietnamese sent an invasion into Laos to topple the government of Prince Souvanna Phouma. It was unknown at the time, but the Vietnamese were building the Ho Chi Minh Trail. According to McNamara, Eisenhower seemed much less concerned about Vietnam than Laos. Eisenhower seemed to be convinced that Laos was the key to Southeast Asia.

Late in 1963, Kennedy became aware of the formation of the Hồ Chí Minh Trail in neighboring countries and planned to send 23,000 U.S. military advisors to Vietnam by 1964. The U.S. communications network (Comint) discovered the trail based upon direction-finding and traffic analysis which allowed them to plot out North Vietnamese messaging stations along the trail.

Kennedy originally supported the policy of sending military advisers to Diệm, but by September 1963, Kennedy saw the ineptitude of the Saigon government and began to have a change of heart. He started distancing himself from Diệm. In response, Diệm agreed to meet with Polish diplomat and Holocaust survivor, Mieczysław Maneli in what became known as the "Maneli Affair" – a proposal to create a federation of both Vietnams that would remain neutral in the Cold War.

Before anything could be done by the US, a group of South Vietnamese Army officers started a coup on November 1, 1963, resulting in the execution of Diệm and his brother / advisor Ngô Đình Nhu. The officers were displeased with the handling of the Buddhist protests during which monks would self-immolate, as well as the deteriorating situation with the DVRN.

Kennedy knew about the situation, and apparently did nothing to stop it. He appeared visibly shaken when he learned of the coup, blaming himself for his lack of action.

Many people cite this as a turning point for Vietnam. Had Diệm lived, it is unlikely he would have allowed the escalation seen under the Johnson administration. In addition, the quality of leadership progressively declined with each subsequent leader. McNamara called the leadership after Diệm “a revolving door: prime ministers were going in and out every few months or few weeks, over a period of time.”

Only 21 days later, an assassin killed President Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson became President.

McNamara said that Kennedy believed the American War in Vietnam would be short lived. Had JFK lived to be presented with the dilemma later faced by Johnson, he might have opted for a de-escalation policy rather than sending in more troops.

On August 2, 1964, North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the U.S.S. Maddox, resulting in minor damage with no U.S. casualties. On August 4th, faulty intelligence by the National Security Agency reported a second attack that did not actually happen. Worried that the North Vietnamese were going on the offensive, President Johnson requested that Congress give him the authority to police Communist aggression in Vietnam. These events became known as the Gulf of Tonkin incident and led to increased U.S. involvement to assist any country whose government was considered in danger of Communist aggression in Southeast Asia. Although Congress never actually authorized war, most Americans still call it the “Vietnam War”, while the Vietnamese call it the American War or the Second Indochina War.

Johnson focused on domestic issues which distracted him from the events in Vietnam. Civil Rights were on the top of his agenda. McNamara said Johnson rarely attended the meetings about Vietnam and had only visited the country once or twice. He seemed determined to maintain the policies of Kennedy and kept his cabinet of advisors. Johnson seemed to give the war in Vietnam little thought as the words of Eisenhower echoed into the policy of a third presidency.

McNamara later said about this incident:

We were certain at the time that the first attack took place. I believe the date was August 2nd, 1964. We made every effort to be certain that we were right, one way or the other -- it had occurred or it hadn't occurred. And it was reported that there were North Vietnamese shell fragments on the deck of the U.S. destroyer Maddox. I actually sent a person out to pick up the shell fragments and bring them to my office, to be sure that the attack did occur. I am confident that it did; I was confident then, I am confident today. That was the August 2nd attack.

On August 4th, it was reported another attack occurred. It was not clear then that that attack had occurred. We made every possible effort to determine whether it had or not. I was in direct communication with the Commander-in-Chief of all of our forces in the Pacific (CINCPAC) by telephone several times during that day, to find out whether it had or hadn't occurred. He had reports from the commanders of the destroyers on the scene: they had what were known as sonar readings -- these are sound readings. There were eyewitness reports. And ultimately it was concluded that almost certainly the attack had occurred. But even at the time there was some recognition of a margin of error, so we thought it highly probable but not entirely certain. And because it was highly probable -- and because even if it hadn't occurred, there was strong feeling we should have responded to the first attack, which we were positive had occurred -- President Johnson decided to respond to the second [attack]. I think it is now clear [the second attack] did not occur. I asked [North Vietnamese] General Giap myself, when I visited Hanoi in November of 1995, whether it had occurred, and he said no. I accept that.

This incident prompted Johnson to escalate U.S. involvement in Vietnam by requesting the U.S. Congress give war authorization. Congress responded by granting President Johnson broad authority. Congress did not debate the issue due to a growing divide among the American people about going to war in Vietnam. McNamara said:

And he was determined -- and as a matter of fact, I was determined -- to avoid the risks that would follow from applying unlimited military force. In addition to a terrible loss of life that would have resulted from that, there was ... a risk of overt confrontation between the U.S. and China and the Soviet Union, overt military confrontation, including the possible use of nuclear weapons. On one or two occasions, the chiefs recommended U.S. military intervention in North Vietnam, and stated that they recognized this might lead to Chinese and/or Soviet military response, in which case, they said, "We might have to consider the use of nuclear weapons." The President was determined to avoid it; I was determined to avoid it. He was fearful that public debate would lead to greater pressure for that, and that's one of the reasons -- not the only reason, but one of the reasons -- he avoided public debate.

McNamara would later cite this lack of debate as a principal reason why the country could never unite over the issue of Vietnam. Had debate occurred, either the American people would have agreed to the war in Vietnam fully aware of their decision or Johnson would have realized the unpopularity of the decision and would have been hesitant to escalate the war.

Johnson initially sent 184,000 troops, which eventually bloomed to half a million over the next couple years. McNamara went on to say:

In any event, it was a very serious error on the part of the Johnson Administration. We did not fully debate the actions that led to the introduction of 500,000 troops, either with Congress or with the public. And that's one of the major lessons: no president should ever take this nation to war without full public debate in the Congress and/or in the public.

By 1965, McNamara had concluded the U.S. could not win a war in Vietnam. McNamara and McGeorge Bundy, the U.S. National Security Advisor to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson from 1961 to 1966 sent a memo to Johnson, stating:

"Mr. President, we're following a course that cannot succeed. We cannot continue solely in providing training and logistical support. We've got to go beyond that, or we have to get out. And we're not certain which of these two alternatives should be pursued. Each should be debated. We're inclined to think we've got to get further in."

Many years later, at a public conversation in UC Berkley, McNamara would question if Ho Chi Minh was ever truly the Communist dictator many in the West would paint him as. At the 49:16 mark, McNamara mentioned:

“Now to illustrate the degree to which we didn't understand the situation in Vietnam at the time, Ho Chi Minh was probably more of a nationalist. I’ll call it more of a Tito than he was a servant or a follower of Khrushchev. We looked upon him as a vassal of the Soviets. He may well have been more of a Tito, a nationalist. In any event he had lived in Paris during World War II. He had lived with this man Obrecht. He was the Godfather of Obrecht's child by the way. Ho Chi Minh, and you can't hardly believe he had been a pastry-cook at the Savoy Hotel in London. He lived in this country for a time. There's a real possibility if we understood him better, we could have avoided this war. …or after it started, we could have terminated it, and it illustrates my point of how little we knew and understand those people”

In 1968, McNamara gave up and submitted his resignation as Secretary of Defense. He saw no way to accomplish the objectives necessary to win a war. The U.S. plan involved sending a combination of U.S. military to defend the south and bombs to apply pressure to the north. It was the hope that eventually the north would come to the negotiation table. America had no offensive objective. The U.S. government feared that a DRVN defeat would draw in the Chinese or the Soviets to escalate the Cold War into a kinetic war and a possible exchange of nukes.

How can a country win a war if it is not willing to destroy the enemy’s ability to fight that war? The answer should be obvious. By the end of the interview, McNamara made it clear that America never had any clear objectives about how to win the war. The war started with a policy of containment and gradually wore down the resolve of the American people. The politicians, the media and the American people saw the war as unwinnable with the constraints placed upon the military and started pushing for military withdrawal. America would need to find another way to stop the growth of communism.

McNamara resigned his position as the Secretary of Defense to become the head of the World Bank. I imagine the stigma of the war stuck with him for the rest of his life. No matter what he did to try to improve living conditions by creating policies aimed at poverty reduction, no one could quite forget the horrors of the war he participated in. In the end, he probably ended up doing more good than harm in his final days working at the World Bank by shifting the focus of the World Bank from the goals of economic growth towards goals of poverty reduction, but no one could ever forgive his earlier transgressions.

Even his own son had trouble reconciling some of McNamara’s more difficult decisions. While McNamara was at the World Bank, one decision in particular that divided father and son was allowing Pinochet to seize power in Chile by favoring Pinochet over the previous Chilian President. While living in Chile, Craig McNamara found himself questioning his father’s politics. Craig later said "I was really upset by that. That was hard to mend.”

After McNamara retired from the World Bank, he finally began his mea culpa; he wrote his famous 1995 book, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam. In it, he told his version of the story, detailing the events that led to the war in Vietnam and his thoughts as the U.S. spiraled into an unwinnable war. The book was incredibly popular with people still looking for an answer to why the U.S. ever entered such a terrible war. McNamara couldn’t give all the answers, but he somehow humanized the entire tragic war.

In late 1995, McNamara met with General Võ Nguyên Giáp, who could be thought of as McNamara’s counterpart on the Vietnamese side, and the two were able to compare notes. This meeting seems pivotal to McNamara as he finally came to terms with all the intelligence errors that caused the bad decisions made during the war. This may have been the final linchpin that turned him from hawk to dove as he became very critical of the 2003 invasion of Iraq under President Bush.

Filmmaker Errol Morris found himself so inspired by the book. that he met with McNamara to discuss making a movie together. The two really hit it off at Morris’s home in the late 1990’s. The film seemed to come out at the perfect time, as America seemed to be preparing to relive the events of Vietnam with the new “War on Terror”. The movie found critical acclaim and won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

At the end of his life, McNamara remained active serving on the board of trustees for a couple Universities and a think tank. He died at the age of 93 in 2009 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. The man seemed to live five lifetimes, with his involvement in WWII; his success in Corporate America; his role as the Secretary of Defense during the war in Vietnam; his tenure as the President of the World Bank; and finally, his post-retirement book and movie. Any of these periods of his life are fascinating by themselves. It is hard to believe so much influence came from just one man.

Fascinating.

Excellent sumation of the American and Vietnam war.

I remember when Deim's wife came to America and visited Harvard University with her bueatiful daughter in 63 and ,she said , please stay out of our country,,you are only making things worse. At the time I was a student and had a staff job at Boston University and one of my highly connected political friends said Jack K was moved by her plea and thought it was time to get out of Vietnam ,somehow ? unfortunately Jack was killed shortly there after .My friend also said Jack thought Max was a blow hart , a real do nothing selfserving car guy ,and was very much over his head in Washington and was influenced by the war- money people ,,That's probably why Max probably got that job later at the World Bank. The American -Vietnam war was a sad turn in human history for all sides. Let's not let that happen again.

U.S.Vietnam Veteran 1966-69