In Vietnam’s long history of fighting back against foreign rule, Đề Thám is one name that really stands out. While most of the country, including the emperor, had surrendered to the French, Đề Thám and his small army kept up the fight for 30 years. His life was packed with daring battles, betrayals, and an iron-willed refusal to back down. There’s a lot of mystery around his story, especially how he died, which only adds to the legend he left behind.

Early Life and Roots of Resistance

Born in 1858 as Trương Văn Nghĩa, Đề Thám came from a rebellious family. His father, Trương Văn Than—later revealed to be Đoàn Danh Lai—had led a peasant uprising against the Nguyễn Dynasty, which ruled Vietnam before the French arrived. After losing his parents, Đề Thám and his older brother were left as orphans. Eventually, he changed his name to Trương Văn Thám, before becoming the legendary Đề Thám.

He moved around a lot before finally settling in Yên Thế, Bắc Giang—the place that would become the heart of his resistance movement. Đề Thám grew up during a time when Vietnam was feeling increasing pressure as the Vietnamese empire was in clear decline. But it wasn’t until he joined the Đại Trận uprising from 1870 to 1875 that he truly started making his mark on history.

The Early Days of Rebellion

By the time the French launched their first assault on Bắc Kỳ in 1873, Đề Thám had already earned a reputation as a fearless fighter. He teamed up with Trần Xuân Soạn, a well-respected general from the Nguyễn Dynasty who was pushing back against French control in the north. Their early campaigns were part of a broader movement against the French occupation, that included uprisings like the Cần Vương movement. While these initial campaigns didn’t bring the French to their knees, they set the stage for Đề Thám’s eventual rise.

Đề Thám participated in the Cai Kinh uprising in Hữu Lũng from 1882 to 1888, a series of guerilla battles that built his reputation as a master of unconventional warfare. By late 1885, he returned to Yên Thế with Ba Phúc, serving under Đề Nam (Lương Văn Nam), who was one of the movement's top generals. In April 1892, Đề Nam was assassinated by one of his own, Đề Sặt. Đề Thám quickly had his general, Đề Truật, take revenge by executing Đề Sặt. The assassination of Đề Sặt pushed Đề Thám into the top leadership role of the Yên Thế movement. Đề Thám revolutionized the movement by unifying other different militia factions into a united movement to oppose the French.

The Yên Thế Uprising

With Đề Thám at the helm, the Yên Thế Uprising became one of the longest and most tenacious guerrilla wars against French colonial rule. For more than three decades, Đề Thám led relentless attacks on French forces. His deep understanding of the northern terrain, combined with his skill in rallying peasant fighters, made him a formidable opponent.

The French threw everything they had at Đề Thám and his army. From large-scale military campaigns to assassination attempts, they tried to break the back of the resistance. But Đề Thám's genius lay in his ability to adapt. By using guerilla warfare, his forces excelled in hit-and-run tactics, blending into the local population and leveraging the dense forests and rugged hills of northern Vietnam to evade capture.

Significant battles such as the battles at Lược Hà, Cao Thượng (October 1890), Hồ Chuối Valley (December 1890), and Đông Hom (February 1892) saw Đề Thám’s forces face off in several battles against various high ranking French officers. Despite facing superior firepower, Đề Thám's insurgents managed to hold their ground, forcing the French to strike peace deals on two occasions.

Two Periods of Peace

In 1894, the French were forced to negotiate the first period of peace with Đề Thám after they experienced repeated failures to crush the movement. They ceded control of four cantons in Yên Thế to him and his army. However, just a year later, the French broke their promises, launching a massive military campaign in 1895 led by Colonel Gallieni.

Gallieni mobilized thousands of troops with artillery support to attack Đề Thám’s army. He even offered a 30,000 Franc reward to anyone who could capture Đề Thám. The French were unable to pursue Đề Thám’s army due to their usage of guerilla war tactics because the army would simply disappear into the forest when cornered. Eventually, the French would start destroying the plantations around Yên Thế, destroying Đề Thám’s support and forcing Đề Thám to accept a second peace deal.

After a couple years of fighting, Đề Thám and his army agreed to the second period of peace, from December 1897 to January 29, 1909. During that time, the Yên Thế insurgents made big moves. They expanded their operations from the semi-mountainous area of “the midlands” to the plains, even reaching into the area around Hanoi. During this time, his forces reorganized and expanded their influence into other geographic areas. Đề Thám founded several resistance organizations, including the “Nghĩa Hùng Party” and “Trung Châu Ứng Nghĩa Đạo,” and began coordinating with patriotic scholars such as Phan Bội Châu, Phan Châu Trinh and many others.

One of the most daring moves during this time was the notorious Hanoi poisoning incident in 1908, which sent shockwaves through both the French colonial regime and the local community. I’ll return to this incident in a little bit because it had huge ripple effects on the movement.

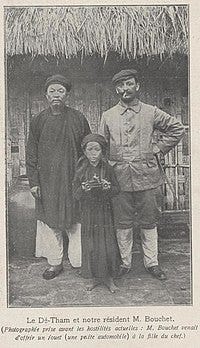

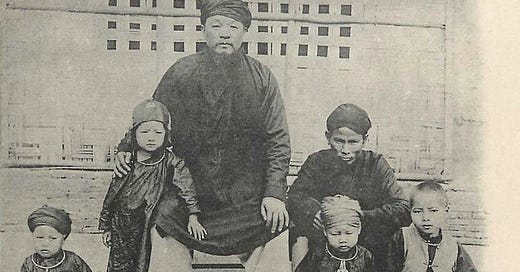

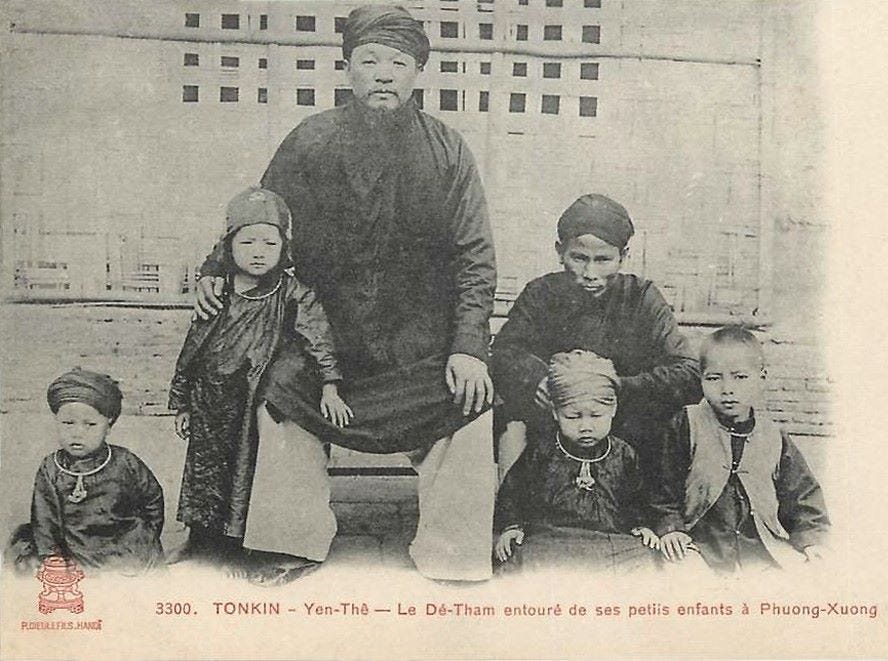

French Photographers Visit

It was during these periods of peace that we are given glimpses into the home life of Đề Thám as French photographers are allowed to visit the Đề Thám fort and are even allowed to take portraits of Đề Thám, his family and various members of the Đề Thám army. My favorite series of real photo postcards was produced by Pierre Dieulefils (1862-1937). He is known for being the most prolific producer of Indochina postcards. He produced a series of postcards (numbered from 3300-3354) documenting the life of Đề Thám along with his army and family plus the French army they opposed. Dieulefils specialized in photographs of:

prisoners and execution scenes

street scenes including some wonderful glimpses into peoples homes or places of business

opium usage scenes

famous architecture

some of the most beautiful portraits of native people in their indigenous outfits and occasionally young women and tribal people in various states of undress

I spend quite a bit of time going through his photographs because in some cases, they are the only photos of ordinary life in Vietnam during the colonial period. It is interesting to see how people really looked during that time and take little glimpses into their ordinary lives.

Click on the link below if you wish to view a separate section I have created to show approximately 50 of the photos taken at the Đề Thám fort. I will caution you, there are scenes of executions and even a couple cards of decapitated heads. You should only view these postcards if you have the stomach for seeing violence that includes real-life dead bodies.

Đề Thám: The Rebel Who Refused to Surrender Photographs - Warning! Contains Violent Images!

Warning! Contains Violent Images! There are several photos of real dead bodies here.

The Hanoi Poisoning Incident

On June 24, 1908, a French officer received an anonymous tip about a plot involving Vietnamese soldiers and civilians planning to revolt in Hanoi. The plot consisted of conspirators made up of the Vietnamese cooks and red-scarved soldiers (Vietnamese soldiers fighting for the French) working in the artillery regiment responsible for protecting the Hanoi citadel. Governor Louis Jules Morel ordered an investigation, but fearing they might get caught, the conspirators decided to act fast. Their plan? Poison over 2,000 French soldiers stationed at the Hanoi citadel, then signal an attack by firing flares to coordinate with anti-French insurgents.

Things didn’t go as planned. On the night of June 27, around 200 French soldiers were poisoned, but before the attack could start, Captain Trương felt guilty and confessed the plan to a French priest. The French immediately got wind of the plot and took action. There were reports of suspicious gatherings around the citadel. The French army were alerted and the Vietnamese soldiers were disarmed before they could fire the cannon shots to start the uprising. The next day, 13 Vietnamese soldiers and cooks were sentenced to death, but none of the poisoned French soldiers died.

I suspect this incident to be the “straw that broke the camel’s back” because in January of the following year, the French resumed hostilities against Đề Thám.

In 1909, the French governor of Tonkin, determined to end the Yên Thế movement once and for all, launched a large-scale attack on Đề Thám's stronghold, sending 15,000 soldiers led by Colonel Bataille. The insurgents faced heavy losses, including the death of Đề Thám’s eldest son, Cả Trọng. Though Đề Thám managed to counterattack and evade capture, it became clear he was facing too large of a force this time. The movement began to crumble as French forces gradually tightened their grip.

The Final Days and Mysterious End

By 1910, the Yên Thế movement was in shambles. Key leaders were captured along with Đề Thám’s daughter. Đề Thám’s forces began to dwindle, so he retreated to his haven in the mountains.

Reports of Đề Thám's death are clouded in mystery. His forces dwindled and he was constantly on the move. In one account, three of his followers, disguised and acting under French orders, approached him in the early hours of February 10, 1913 and killed him and two of his guards while they slept. The French displayed Đề Thám's head at Yên Thế Palace to intimidate the local people.

Some people doubted the official story, citing several inconsistencies. The French only allowed the head to be displayed for two days before burning it to ashes and dumping it in a pond, with no photographs allowed. A former bodyguard of Đề Thám, Ly Dao pointed out discrepancies when he noted that the head on display didn’t match Đề Thám’s distinct physical features. There was even a rumor that the head belonged to the abbot of a local pagoda who resembled Đề Thám and had disappeared around the same time.

Any followers who were not captured started to disband and all word of the rebel group slipped into obscurity. In a way, it doesn’t really matter if the head belonged to Đề Thám or not because the revolution was dead.

A Star is Born

There is an interesting side story of the many reports of Đề Thám’s surviving daughter, Hoàng Thị Thế. She was the child of Đề Thám’s third wife, Đặng Thị Nhu. After the presumed execution of Đề Thám, she was adopted by the Governor General of Indochina at that time, Albert Sarraut and renamed Marie Beatrice Destham. At the age of 12, she was sent to France to study at the Jeanne d'Arc boarding school in Biarritz (a lovely coastal town near Spain).

Hoàng Thị Thế evidently had an amazing life, being elevated highly within French elite circles due to friends she met because of her stepfathers connections. If one is to believe everything in her memoir, published in 1974, she was the “it girl” of Paris from the 1910’s to the 1930’s. I found the articles of her biography a little too fantastic to be included as only a minor character in her father’s story. I have been looking for her book, but it seems it is out of print and appears to have been published in Vietnamese. If you have read it, please let me know. You should check out her Wikipedia page. Here are some of the highlights:

She had an affair with a high-ranking official in Hanoi, which became the shock of the city.

She was involved in a car accident driven by André Tardieu (chairman of the Council of Ministers).

She became a famous actress starring in several major studio films.

She became a national champion in flying discus shooting.

She had three children.

She reportedly even received a marriage proposal from Hồ Chí Minh, but this was later denied by the Vietnamese government.

Hiroo Onoda: The Soldier who didn’t know the War Ended

As I hear the story of Đề Thám, I can’t help but think of World War II soldier Hiroo Onoda, the Japanese soldier who continued to fight for decades after World War II ended.

Hiroo Onoda was a second lieutenant in the Japanese army when he was sent to the Philippines in 1944. He had a clear mission to lead a guerrilla warfare campaign on Lubang Island, sabotage enemy airstrips and prevent Allied forces from landing at any cost. But most importantly, Onoda and his men were given strict orders never to surrender or take their own lives. For almost 30 years, Onoda and a dwindling number of comrades kept up their guerrilla campaign, raiding villages and attacking perceived enemies.

When the war ended in 1945, Onoda and his men were never relieved of duty. Leaflets were dropped, urging them to surrender, but they assumed it was enemy propaganda. As the months turned into years, Onoda and his comrades kept up their guerrilla campaign, raiding local villages for food, attacking anyone they believed to be enemy forces and generally causing mayhem on Lubang Island.

Over the years, one by one, members of Onoda’s group either surrendered or died. By 1972, Onoda’s last remaining comrade, Kozuka, was killed in a skirmish with the local police. That left Onoda as the sole survivor of his group.

It wasn’t until 1974, when a Japanese adventurer named Norio Suzuki went looking for him, that Onoda’s bizarre saga came to an end. Suzuki, armed with nothing but a camera and a dream to meet the legendary holdout, found Onoda hiding in the mountains. Despite Suzuki’s efforts to convince him that the war was over, Onoda refused to surrender until he received direct orders from his commanding officer.

Suzuki returned to Japan and located Major Taniguchi, Onoda’s former superior, who had long since retired and become a bookseller. Together, they flew back to the Philippines, where Taniguchi officially ordered Onoda to stand down. Onoda finally surrendered in 1974, nearly 30 years after the end of World War II.

Onoda’s surrender made headlines around the world. He turned in his sword, rifle, and remaining ammunition, as well as the dagger his mother had given him to use for suicide if necessary. Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos granted him a full pardon for his actions during his time in hiding, including the deaths of civilians in raids.

Onoda returned to Japan as a hero, but Onoda became unhappy at receiving such attention (or maybe feeling the guilt for pointlessly killing 30 civilians). He believed the country had begun a withering of traditional Japanese values. Onoda wrote an autobiography titled No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War and later moved to Brazil, where he became a cattle farmer. He spent the rest of his life splitting his time between Brazil and Japan, where he founded a nature school to teach young people survival skills. He died in 2014 at the age of 91.

Soldiers Who Refuse to Give Up

At first glance, Đề Thám and Hiroo Onoda seem like very different figures. Đề Thám fought for national liberation, while Onoda was a loyal honor-bound soldier of the Japanese Empire. But both men showed an incredible sense of duty and commitment to their causes. Both spent 30 years continuing to fight, even when everyone else had given up decades earlier. But there is something different about these two. What makes these men willing to continue the fight long after everyone else quit?

Sometimes there are war stories about militia groups who refuse to give up despite the fact that their governments no longer exist. The same thing happened during the US Civil War. Even after General Robert E. Lee signed the articles of surrender agreement at Appomattox Court House followed by the dissolution of the the Confederate cabinet and surrender of Confederate President Jefferson Davis a month later, Confederate troops continued to fight for approximately six additional months.

For some, it seems war is about something much larger than national pride or ideology. These people seem to be honor bound to fight until death.

Legacy of Đề Thám

Đề Thám's legacy has grown from freedom fighter who resisted French invasion of his beloved country into the world of Vietnamese folklore. It seems that initially, the French perceived him to be a warlord, but as time went on, a mythology grew around him that painted him as a anti-colonial revolutionary.

As I read the Vietnamese sources, Đề Thám becomes a type of proto-resistance fighter, coordinating with many of the popular resistance leaders which would emerge in the early 20th century. I take this with a grain of salt because the stories of resistance leaders in North Vietnam seemed to take on a mythology of their own as they seem to become retconned to inspire a new generation of resistance fighters.

At some point, the mysteries surrounding Đề Thám became a little too coincidental to be believed and drifted further into the realm of myth than reality. I found myself occasionally thinking, is this man really at the center of every proto-revolutionary group? In the end, I simply decided to leave out the portions of the story I found to be too fantastical. Sometimes, it is important to just enjoy the story and put the man into his historic place among the many revolutionary leaders of Vietnam.

Đề Thám’s name lives on through streets, schools, and monuments, reminding generations of his sacrifice for independence. His fight paved the way for future resistance movements demonstrating effective guerrilla warfare tactics that influenced the Việt Minh and Việt Cộng, who ultimately succeeded in driving out the French and Americans. Like Hiroo Onoda, Đề Thám’s story shows that for some, the fight for a cause doesn’t end until the last breath.

Another war which lasted so many years, I don’t see where either side benefited. I haven’t looked at the photos yet, I am interested in seeing them, but not so much the decapitations, probably not much different to what we are faced with on Netflix!! Once again a very interesting read and very comprehensive.

Can you explain more about his turban and his family's turbans? I'm caught thinking about 19th century Chinese movements like the red turban rebellion.